KNOCKANDO, MEIGLE, TAIN, AND THE SPOKED WHEEL (1)

In which I begin to look at the history and traditions of the spoked wheel, and how it might be functioning in a Pictish context

Knockando sits on the north bank of the Spey river, a region littered with Class I symbol (pagan) stones. Today, the church at Knockando has three large stones, two of them Pictish symbol stones, the third a stone with Norse runes deeply carved into it.

These symbol stones are of particular interest. The first has a spoked wheel on it, one of only two examples in Pictland, and two crescent/V symbols, making three symbols rather than the usual symbol pair.

The second has a ‘flower’ symbol below a snake, and this ‘flower’ symbol occurs at places that appear to be ritual locations rather than settlements.

The third stone has Norse runes that read SIKNIK, the name of a man that also occurs at Sanda, Södermanland in Sweden. The Norse however didn’t settle this far south, so what has drawn this Norseman down to Knockando? And why would they go to considerable effort to carve deep runes at just this place?

Large symbol stones, with special symbols, another with Norse runes, all this says a closer look at Knockando is warranted. Part One of this blog will look at the spoked wheel symbol and the connection to sanctuaries. Part Two will search for further evidence of a sanctuary at Knockando. Part Three will look at the ‘flower’ symbol on Knockando2, and then pull together why these spoked wheel locations are so special.

The real spoked wheel and the Celtic icon

Thousands of small votive spoked wheels have been found all over Celtic Europe and the insular world. So before we start to ask what a spoked wheel symbol might mean to the Picts, we need to go back and look at the history of the wheel, and the icon of the spoked wheel.

The real spoked wheel was not invented until 2200–1550 BCE, although the first wheel made of a solid round block of wood had been invented earlier in Mesopotamia around 4500–3300 BCE. The history of the wheel can be read here.

The spoked wheel is an icon whose significance predates the real spoked wheel. For instance, Dowth with its Neolithic spoked wheels carved on its kerbstone, was built c.3200 BCE so well before the invention of the actual spoked wheel.

The spoked wheel continued as a key Celtic icon, perhaps the Celtic icon. Thousands of votive spoked wheels have been found in sanctuaries from Britain to Thrace. They start in the middle Bronze Age (c.2100-1550 BC), continue on through the Roman era, only falling out of use with the arrival of Christianity. The icon has long associations with the sun, perhaps an icon of the sun at the centre of the revolving universe.

Around 300 BC a change sweeps the Celtic lands, and spoked wheel amulets stop being put into the graves of women, from then on only male graves contain them. This may be connected with the arrival of the new (male) thunder god, Taranis, whose Romano-Celtic statues hold both a thunderbolt and a wheel. Under Romano-Celtic interpretatio, Taranis was linked with Roman Jupiter, another male god controlling thunder.

From the middle Iron Age, the spoked wheel is prominent on coins, and in depictions of horses and chariots. The icon has become linked with the real wheel, thunder, wheeled chariots, and in western Europe at least, Taranis.

The spoked wheel icons start with only 4 spokes, later moving to 6 and 8, 8 being the number of spokes on the depictions of Irish chariots. Both Pictish symbols have 12 spokes, showing that it still retains its philosophical status, perhaps the 12 segments of the zodiacal sky.

More information on the spoked wheel icon and pictures can be seen here.

So, finding the Picts with a spoked wheel as one of their symbols is not surprising, it would have been surprising had they not. But the tradition of the spoked wheel as a symbol of the sun is long and complex. It’s history gives us solid clues, but makes teasing out what the Picts exactly meant by their own spoked wheel somewhat complicated.

The Picts aren’t the only ones carving a spoked wheel icon on stones during the Iron Age. Here is the Estela de el Viso, Cordonba, Spain. Note how similar it is to the Knockando example, with a dot in each segment, except in having 10 spokes rather than 12, 4 on one side and 6 on the other.

The Pictish Spoked Wheel symbol

Ardjachie and the Tain sanctuary

Beside the Knockando 1 spoked wheel symbol, there is just one other on a Class I Pictish symbol stone, at Ardjachie just to the west of the great sanctuary of Tain, Easter Ross. The stone itself is a re-used ancient stone covered with ancient cup-marks. A spoked wheel could have been sourced from an ancient passage mound where Neolithic spoked wheels have been found, but the depth of carving of the Ardjachie spoked wheel is the same as the other symbol, so it is a newly carved symbol on an ancient cup-marked stone.

The Knockando stone doesn’t have cup-marks as such, but unusually the stone is pitted, giving a similar impression. The ‘pits’ are even copied manually inside the segments of the spoked wheel itself. If we think of the spoked wheel as representing the sun in the sky, then the cup-marks are the stars in the sky. Interestingly, there are cup-marked stones just to the north of Knockando at Carn na Leacainn, from lec 'flagstone' (information from Douglas Ledingham).

The other symbol on the Ardjachie stone is a stepped-rectangle, a couple of which are also found at the large nemeton that stretches from Dalnavie ‘Dale of the Nemeton’ to Nevyn Meikle ‘Great Nemeton’, just across the hill pass to the south of Tain, suggesting that the Tain region was part of the Great Nemeton in Pictish times. Later of course Tain would become famous as one of the great sanctuaries of Scotland (CPNS, Watson, p249).

Meigle and its three spoked wheels

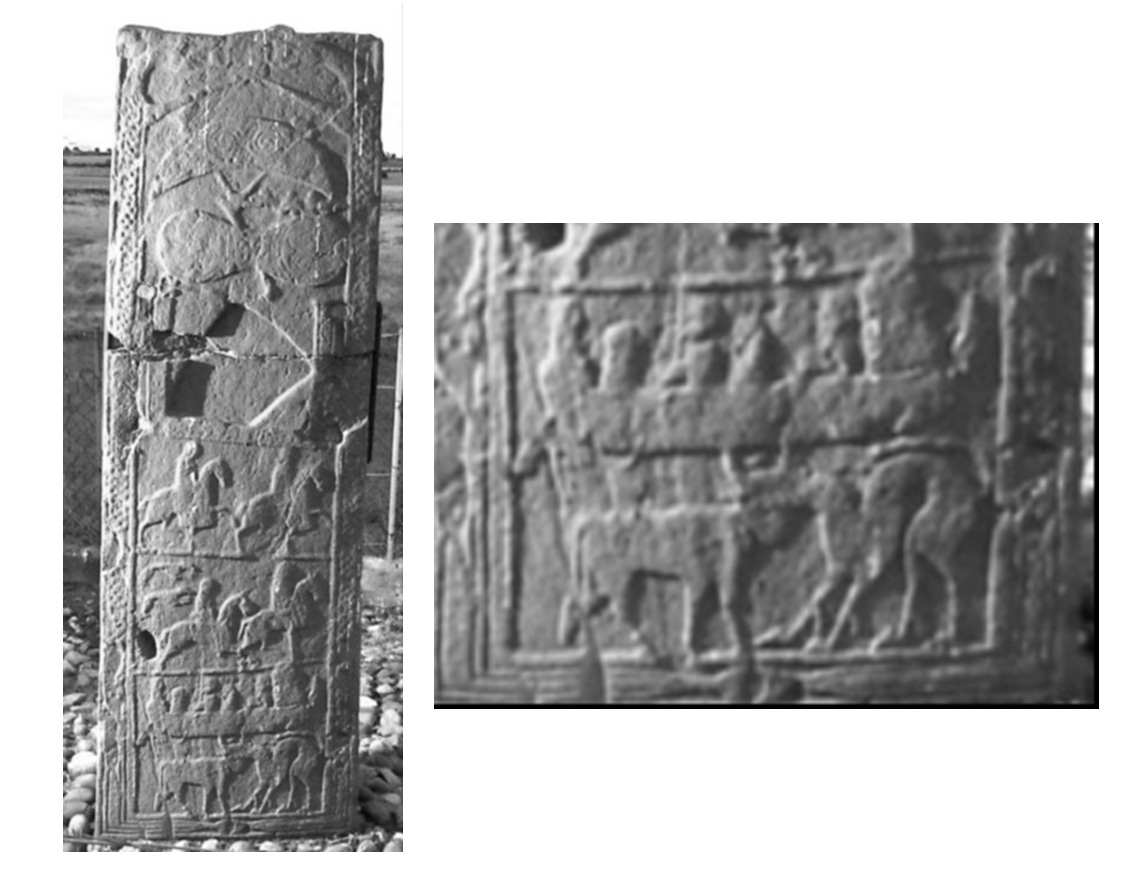

There is another spoked wheel, not a symbol but the wheel of a carpentum with a cover on a panel at Meigle, since lost. The wheel is placed centrally on the carving to underline its importance. The carpentum was a ritual chariot used by Roman women. A passenger is drawn large to emphasis their importance, but the stone is too eroded to make out further details.

There was a large cross found, then also lost, at nearby Newtyle, with another chariot on it (Canmore ID 268544) . In 1569, Henry Sinclair, Dean of Glasgow, described the carvings: “ane cors at the heid of it, and ane goddess next that in ane cairt, and two hors drawand hir, and horsemen under that, and fuitmen and dogges, halkis and serpentis…” Although no further details were given about this ‘goddess’, we would have to presume Sinclair must have been able to see details to be so specific.

Then to the north of Meigle, at Alyth, there is a fragment with a double-disc/Zrod on it. This symbol is the second most frequent Pictish symbols, and today we have over 50 of them. Uniquely, on the Alyth stone the inside of the remaining disc has been turned into a spoked wheel. This means that we have effectively three spoked wheels icons around Meigle.

The Picts marked this sacred space around Meigle with a number of symbol stones and later Christian crosses, leaving us in no doubt of the importance of this place. Meigle seems to be part of another large nemeton similar to the Great Nemeton in Easter Ross, stretching from Newtyle (a name that may contain new-, a later form of ‘nemeton’), through Meigle, past Eassie and Nevay (another nemeton name) to the shore of the old Loch of Forfar at Cossans. And it is here that we have another extraordinary cross, this time with a boat, unique on Pictish stones.

What is so special about this nemeton around Meigle? The boat icon is located near the outlet of the Dean Water from the old Loch of Forfar, now much diminished by recent drainage. This Dean (‘goddess’) stream is very unusual in eastern Pictland, for it flows to the west. It runs along the length of the nemeton to join with the Isla just to the north of Meigle. Regions who had access to the western seaboard had islands whose mythology and practices reflected the belief that the dead moved with the sun to the west. Famous examples are Skellig Michael, Iona, House of Donn, Brough of Birsay, St Ninians Isle. But Pictland had no such access to the west, only the Dean Water flowing perversely westward. This is one of the few places in Pictland (the only one I know of) where the sun’s journey to the west can physically play out in the land.

Beyond the western point of the Dean, there is a monumental barrow cemetery at Bankhead of Kinloch.

How does the boat, and the chariots and spoked wheels, fit into this picture? Again we need to go back a little and look at history. In the Bronze Age, petroglyphs show boats with the spoked wheel tethered above it, the sun riding across the sky in her boat. A good summary with references is here.

In later years, mythology and Romano-Celtic icons continue this theme of the sun in her boat drawn by waterbirds.

But as the horse and chariots move across the land, the sun is given a horse, or a horse drawn chariot, to fly through the sky as well. And it is with the sun that the dead journey onwards to the west.

This returns us to the theme of the spoked wheel that we started with, the sun at the centre of the sky. The sun moving to the west along the Dean Water, on her boat, and in her chariot. And at the far west, with the setting sun, the dead in their barrows.

One last question might be asked: why is it at Meigle that they opt for iconograpy rather than just using the spoked wheel symbol? The answer is that all these stones come from the period of the introduction of Christianity. The spoked wheel all over the western world ceases to be used once Christianity takes hold. Under the influence of cultures of the near east which had already turned the female sun into a male entity, the new Christ was instantly covered with the power and light of sun symbolism. The ancient female sun had been usurped and would eventually disappear except for hints in old stories. At Meigle, this process is underway, the sun symbol is now the emblem of the new male god, but they haven’t yet pushed their sun goddess out of existence.

The sun goddess and her chariot

We can’t let this subject go before asking, who is the sun goddess in Celtic/Pictish lore? As expected there are several candidates, who may be the same sun deity under a different name, or different aspects of the sun. I will only mention two here, Epona and Aife, because both these deities are pictured with chariots.

The horse goddess Epona has three standard forms in Roman-Celtic art, one sitting side-saddle on a horse, the second seated with horses either side of her, and the third in a chariot. This is where the Celtic worldview is complex to comprehend, for the sun is drawn by horses, but she is also the goddess of horses, and the horse itself.

On the Gundestrup cauldron we have a female, seated on a cart, with spoked wheels, again likely a depiction of Epona, although as with the rest of the plates on the cauldron, her horses have been swapped for more exotic elephants and hippogriffs.

But in Irish and Pictish lore, the sun goddess is Aife (modIr. Aoife). She is perhaps best known as riding her chariot with the children of Lir, god of the sea. However, as she reaches a lake she turns the children into swans, the waterbirds, the same birds that traditionally pull her sun boat.

Aife is again associated with waterbirds, when she herself is said to have been turned into a heron or a crane, after which she spends her time in the realm of the sea god, Mannanan mac Lir. Here again, she is the deity of waterbirds, but also a waterbird, the same ambiguity that we saw previously with the horse.

But Aife is also the goddess who ‘loves her horses and chariot above all else’. Aife (Radiant) has a sister Scathach (Shadowy) who is the tutor of young warriors in the art of war and love, and in this story Aife and Scathach reside in Alba. Here Aife is the radiant sun of the day sky riding in her chariot, her sister and rival Scathach the dark sun of night.

Knockando, Tain, and Meigle : spoked wheels and sanctuaries

This blog started off to ask what a spoked wheel might be doing at Knockando, but it’s resulted in a whirlwind tour of sun mythology and other spoked wheels.

So far, we have found the spoked wheel, as ancient icon and symbol, at Ardjachie near Tain, one of Scotland’s major sanctuaries and part of a large pagan nemeton. And we have a group of three spoked wheels at the major southern nemeton of Meigle-Nevay-Cossans, one spoked wheel within the double-disc/Z symbol at Alyth, and the wheels of two chariots at Meigle and Newtyle. This fits with the thousands of votive spoked wheels found in sanctuaries across the Celtic world. The question now is, is Knockando with its spoked wheel also an ancient nemeton, a sanctuary that we have lost sight of?

In the next part of this blog KNOCKANDO: LOOKING FOR A LOST SANCTUARY I will take a closer look at the area of Knockando to see if there are any traces of a sanctuary still to be found, and if so, what might its function have been?

Interesting stuff Helen. But what stopped me in my tracks was the image of the Spanish stone, Estela de El Viso, which seems to have a mirror and comb on it. I thought this symbology was unique to Pictish stones.

Do you have any research sources on this stone and its symbology? I couldn’t find anything via Google