PICTISH WOMEN and the MIRROR and COMB

exploring whether the mirror+comb indicates the presence of a woman on Pictish stones?

In this blog, I’m going to look at the association of the mirror and comb to women on Pictish stones, to see how far we can take this idea.

On Class I stones, there are 34 examples of a mirror+comb accompanying a pair of symbols, roughly 1 in 5. The mirror, or the mirror+comb, always occurs as modifying elements to the main symbol pair. In a previous blog, I’ve shown how they interact with the main symbols to acknowledge a change in order or precedence.

But on Class II stones, the number of mirror+comb examples drops to 11 symbol stones, plus 5 stones on which the mirror+comb occurs without any main symbols. Of itself, this warns us that the function of the mirror+comb may be changing in this later period.

the mirror+comb with icons of women

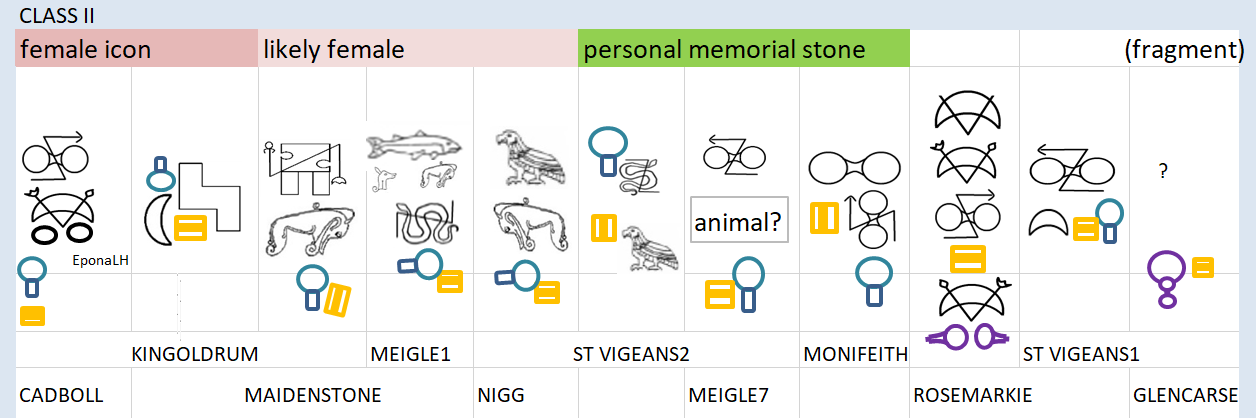

On Class II stones, the mirror+comb is on a number of stones with an icon of a woman, suggesting there is some sort of linkage going on here. Some of these stones also have symbols, some don’t. So what I will do first is look at each of these stones.

This issue of whether or not we are actually looking at a woman hasn’t in the past been without dispute. This seems to me partly an issue of wanting everything to be ‘biblical’, and partly an issue of not looking at the wider context of Pictish artwork to see what depictions of women in their day were like.

The Hilton of Cadboll stone was located at a small chapel on the southern coast of Easter Ross, probably part of the Portmahomack monastery lands. The chapel, now in ruins, was dedicated to Mary. The mirror+comb is divided off from the main symbols and placed beside a female rider seated facing the front.

The portrait of the woman is a typical Romano-Celtic portrait of Epona, the horse goddess. Epona is uniquely for a Romano-Celtic deity portrayed sitting side-on on a horse, she wears some sort of head veil, her robes are long with folds. (A summary of Epona types is here.)

Pictish art in general has many aspects to it that show it is influenced and evolving from Romano-Celtic artwork. Epona was a popular deity throughout the Roman empire, and there are inscriptions and portraits of her in Britain as far north as the Antonine wall so there is every reason for the Picts to also have seen her portraits and held her in esteem.

The identification with Epona is pushed back on by some people, because this stone has a Christian cross on the reverse and they feel the need to interpret everything in a biblical context, but we don’t actually know how the Picts were integrating their pagan worldview with the new faith. One picture of Christ has been presented as evidence for him portrayed in the female fashion, side-saddle, however on closer inspection the figure is riding astride and only his face is turned out to the viewer.

The depiction of Epona isn’t the only Romano-Celtic icon on the Cadboll stone, there is also a pair of trumpeters here and on Aberlemno3. No such instrument is known otherwise from insular Celtic art, language, or archaeology, but this long straight trumpet is well known in both Roman and Greek art and tradition. The Romans depict tubercines (Lat.) or hierosalpiktes (Greek), sacred trumpeters, usually in pairs, as taking part in cult rituals, usually funereal, and this association is likely what is being called upon on the Pictish stones. (Here is an article about these trumpeters.)

The importance of this continuing influence of Romano-Celtic art, in both form and meaning, cannot be understated. It should help us going forward to better understand the context of Pictish art.

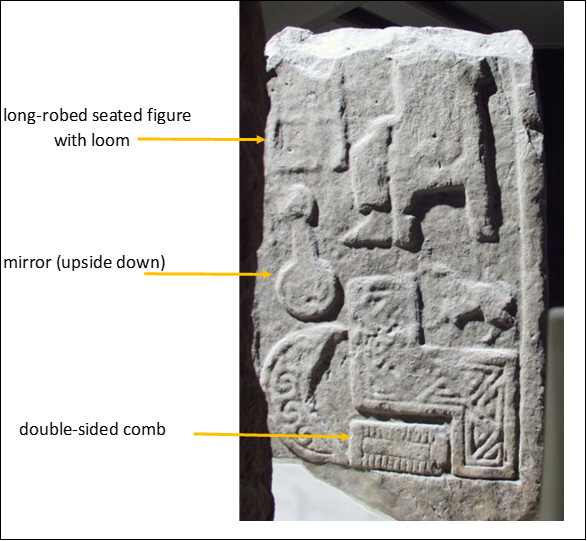

The Kingoldrum stone has the crescent and stepped-rectangle symbols interwoven with a mirror +comb. Above is a seated figure in front of a loom. Assuming weaving is largely a female occupation, as it commonly is in mythology as well, this seated figure is a female. Kingoldrum was dedicated to Saint Medan, whose origin and gender is unclear.

In Romano-Celtic art, women are most frequently portrayed seated, with long robes in folds. Men are rarely depicted on seats. The Picts are continuing this typical form of depiction for women in their art. Eventually, a change would come in illuminated gospels in which Christ and the evangelists are sometimes seated, but there is not the slightest hint that any of these Pictish seated figures are Christ or his disciples. In fact, there are no New Testament depictions at all on the Pictish stones, possibly because they are working in an iconoclastic period when such artwork was the centre of fearful arguments and threats.

The implication of this Romano-Celtic way of depicting women may well be that we need to question the gender of any Pictish seated figure or any figure in full-length heavy robes.

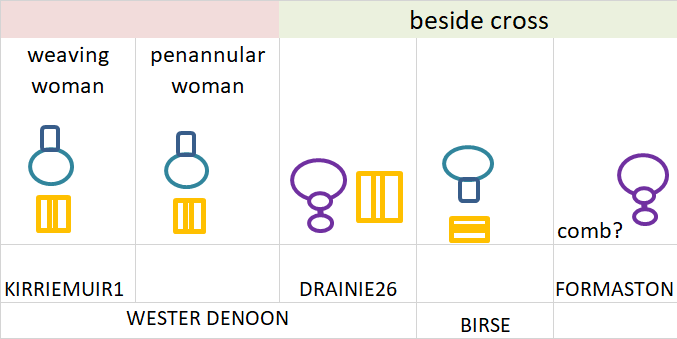

Not far from Kingoldrum is Kirriemuir1, a stone with a mirror+comb, but this time without symbols. Again we see a long-robed figure, seated on a high-backed chair, with a loom. Her hairdo is also worth a mention, reminiscent of Star Wars Princess Leia, two high knots or pigtails. Kirriemuir has a traditional dedication to Mary, just as we saw with Hilton of Cadboll.

Wester Denoon has a mirror+comb but no symbols, and a standing female. The woman wears a penannular brooch at her waist as Celtic women did, and she has an embroidered hem on her dress, with a pleated top or shawl. Another fragment of a cross slab was also found here, but there is now no trace of a church or dedication.

Other Class II stones with a mirror+comb

So far, we have seen some Class II and III stones with a mirror+comb and female iconography. To test out if this is a valid association, we can next examine all the other CII and CIII stones with a mirror+comb from the same period.

The first thing to say is that despite all the common icons of men, riding and hunting, there is no male iconography on any of this group of stones. Not all have explicit female iconography, but none have male. It seems reasonable then to propose that if the mirror+comb is signifying a female association at this late period, a burial or a female function, then the same holds true for the other examples from the same period.

Meigle1 does have some riders on its symbol side, but these are so badly executed and organised that they would appear to be a later addition. The lower left rider however could possibly be a female, although it’s too eroded to be sure (thanks to Erica Birrel for pointing this out). The traditional story of the stone is that it stood over the gravemound of Vanora, the Pictish form of Findabarr/Guinevere.

The Maiden Stone, Chapel of Garioch, also has a female story attached to it, that it is a girl turned to stone after she lost a bet with the devil, that she could finish her baking before he built the road to the top of Mither Tap, a road which does exist. The stone also has a female centaur above the symbols.

Nigg, like its neighbour Hilton of Cadboll, possibly has an eroded mirror+comb in the upper right corner of the ‘hunt’ panel. The rider here is too eroded to be able to tell their gender, although it may be that here we have another Epona icon.

The great cross slab of Rosemarkie has four symbols, the bottom crescent/V with a comb above it and two mirrors below. The church is said to have been founded by Moluag of Lismore, so it’s a little surprising to see a possible female association on this stone. There are no human icons otherwise on the stone to give us a clue. Perhaps the story of Rosemarkie is a little more complicated than has come down to us.

The new fashion of personal memorial stones

As we move close to the end of the period of symbol use, a new fashion is being introduced to the Picts and their neighbours – people start being buried around a Christian church. This trend leads to personal memorial stones, sometimes even with inscriptions, appearing by the early 700s (we’ll see in a moment that in Anglo-Saxon graves, this trend is complete by 700, with grave goods no longer fashionable). Up to this time, Pictish stones had usually been quite large stones, often around 6 feet high, rarely more than one at a church site, but now there are a series of smaller stones, all roughly one metre high, and often located in a group at just a few key churches. If symbols had represented personal names, we might have expected memorial stones to encourage the use of symbols, but they don’t, instead memorial stones move swiftly past the point of any symbol usage.

A few of the mirror+comb stones fit into this new category of a personal memorial, Meigle7, Monifeith1, and Drainie26, suggesting these are memorial stones associated with a woman.

The Monifeith1 stone with symbols and a mirror and comb is part of a post-shrine, so this may be a memorial for a woman. Interestingly, another memorial stone, Monifieth2, has what appears to be a small icon of a woman with cow horns, although this stone has symbols but does not have a mirror+comb. The church is dedicated to Saint Regulus, whose story tells he brought the relics of St Andrew to Pictland, along with a number of women, including Triduana.

Another memorial stone is the Meigle7 fragment, with a comb just visible but its mirror on the missing part.

Using the mirror+comb without accompanying symbols

The mirror+comb until this point in time had only ever been used as extra modifiers for the main symbol pair, yet right at the end of symbol usage, the mirror+comb is suddenly found on a few stones without main symbols. The implication is that these stones too are now specifically associated with a female.

But beyond this, it means that the mirror+comb does have a distinct significance of its own, and that it has a female association. The question though, is how far back does this female association go? Are all symbol stones with a mirror+comb, both CI and CII, somehow indicative of a female association? Or, is this a new focus and function for the mirror+comb in the CII period?

A few other interesting things are happening here. Firstly, the mirror is now upside down and beside a female icon, on Kirriemuir1, Wester Denoon, and Kingoldrum.

The next step sees the mirror+comb moved away from iconography on the stone’s reverse side to the cross, and placed beside the lower stem of the cross on Drainie26, Birse, and Formaston. It’s not just the main symbols that are missing here, but all iconography except the mirror+comb.

Drainie 26 is a small memorial stone from Kinneddar with a mirror+comb but no symbols, suggesting this is a gravestone of a woman. The monastery of Kinneddar is one of a small number of churches which has a group of these small memorial stones. There is only this one example with a mirror+comb though. Birse and Formaston also have features of a late CII/CIII stone, and both have a mirror+comb without symbols.

This is the last-ditch attempt to retain use of symbols as such, the next step being to just depict the cross alone, or occasionally with a name inscribed in ogham or insular script.

Female icons without a mirror+comb

So far, we have some CII stones with icons of women and a mirror+comb, and other CII stones with a mirror+comb which do not have any iconography that tells against this female association as none have male iconography. And, we also see that a mirror+comb continues to be used on small personal memorial stones or gravestones, and even continues without any accompanying main symbols, all suggestive that these memorial stones are now burial stones for a woman.

Another test we can apply is to check whether any other female icons occur on stones that do not hold a mirror+comb. Actually, we should also check that the Picts would include women on stones, after all it’s not a given that a particular culture would be open to the idea.

Women in this period wore a pair of brooches on their shoulders, joined by a chain or tie, to hold their cloak over their tunic. On Invergowrie1 and Meigle29, figures are wearing such a pair of shoulder brooches and so can be identified as women. This also shows us the type of cloak worn by women, the typical heavy pleating or folding of their clothes, and in the case of Meigle29 the tunic has a decorated hem. The figure on the left of Meigle 29 is only partially visible but is probably another woman as she has the same attire and sits on a high-backed chair, so this stone originally would also have had three female figures. Meigle14 also has figures in similar pleated robes with decorated hems, although no brooches are visible, and again we have women in a group of three. All these female aspects may help us to identify other potential women.

These disc brooches have only been found in Anglo-Saxon regions and the continent. In Celtic regions, including Pictland, penannular brooches are the elite items found in archaeology. The likelihood then is that these Invergowrie women are Anglo-Saxon, although it can’t be ruled out that they are Picts who have chosen an Anglo-Saxon mode of dress.

Paired disc brooches have been found in many Anglo-Saxon female graves, but they become rarer towards the end of the 7th century, after which they disappear from graves completely. This trend is tied to the sudden lack of grave goods in Christian graves, and to some extent a change in attire. Disc brooches do continue through several more centuries beyond 700 AD, but now they are more elaborate, expensive, elite and rare items. Men too are wearing disc brooches, but only a single brooch, either pinning a cloak on one shoulder, or centrally at the neck. Only women wear a pair of brooches on each shoulder.

(I haven’t been able to find any examples of a disc brooch found in Pictland, but I can’t be sure. None of the maps in this video show a Pictish find.)

Though there are several depictions of men wearing a single disc brooch from later centuries, I haven’t been able to find a single picture of an Anglo-Saxon woman wearing a brooch pair. It’s known that women wore a brooch pair at the shoulders as they are found in this position in graves. It looks like these two Pictish portraits of women wearing a pair of brooches are unique in all Britain, and so of major historical significance.

Women are depicted in several different contexts on other Pictish stones, although these are now all past the period of symbol usage - the later 700s onwards. On a small fragment from Abernethy we have three nuns, and on the side panel of Sueno’s stone half naked mermaids with intertwined fish-tails.

The Inchbrayock stone has a seated women who is pregnant. The other figure being hit or blessed with a jawbone is likely a female too. The location has dedications to a number of female saints.

Seated figures with heavy robes also occur on a number of other stones, and the chances are that most, if not all of them are women. Note the pudding-basin headdress on the Fowlis Wester figure, and the same thing under the hood on the Abernethy nuns.

Perhaps the most interesting are a group of stones which have a pair of seated figures on high-backed chairs, including St Vigeans11, St Vigeans10, Lethendy and Aldbar. The likelihood is that these are a pair of seated women. These stones date from the same CIII period where a number of small memorial stones have a pair of male horsemen on them. Why figures come in similar pairs is not understood.

Summing up the picture

From all the above examples, we can say with confidence that many Pictish stones have female icons on them, possibly even more examples than I’ve shown here. The Picts are depicting women on their stones in several different situations which will be reflecting different roles or functions. The overall picture is of a society where women are performing active and elite roles, and are respected and accepted in those roles. Most of the stones with women don’t have other men on them, although some do, so these women are not just passive appendages of their husbands, but they are acting in their own right.

But, where does that leave us with the question of the function of the mirror+comb? With the mirror+comb placed beside a main female figure on several stones, and the mirror+comb on several other stones all without male icons, it’s reasonably safe to assume that all late CII and CIII stones with a mirror+comb have some sort of female association.

Which takes us a step forward in our understanding, but still leaves other questions to answer. What exactly is that female association? Are these just female burials? Or memorial stones for female patrons? Or depictions of female deities or saints? Or are they referring to a particular female role or function?

But perhaps most critically, does this female association for the mirror+comb go all the way back through the CI pagan stones as well?