SYNTAX OF THE PICTISH SYMBOLS (PART 2) : THE ORDERED LIST

Identifying how symbols are organised in a ordered list or matrix

Here I’m going to investigate how the Pictish symbols are part of a closed and ordered list, not a random open corpus of symbols. And how the order of symbols on a stone reflects their order in this closed list.

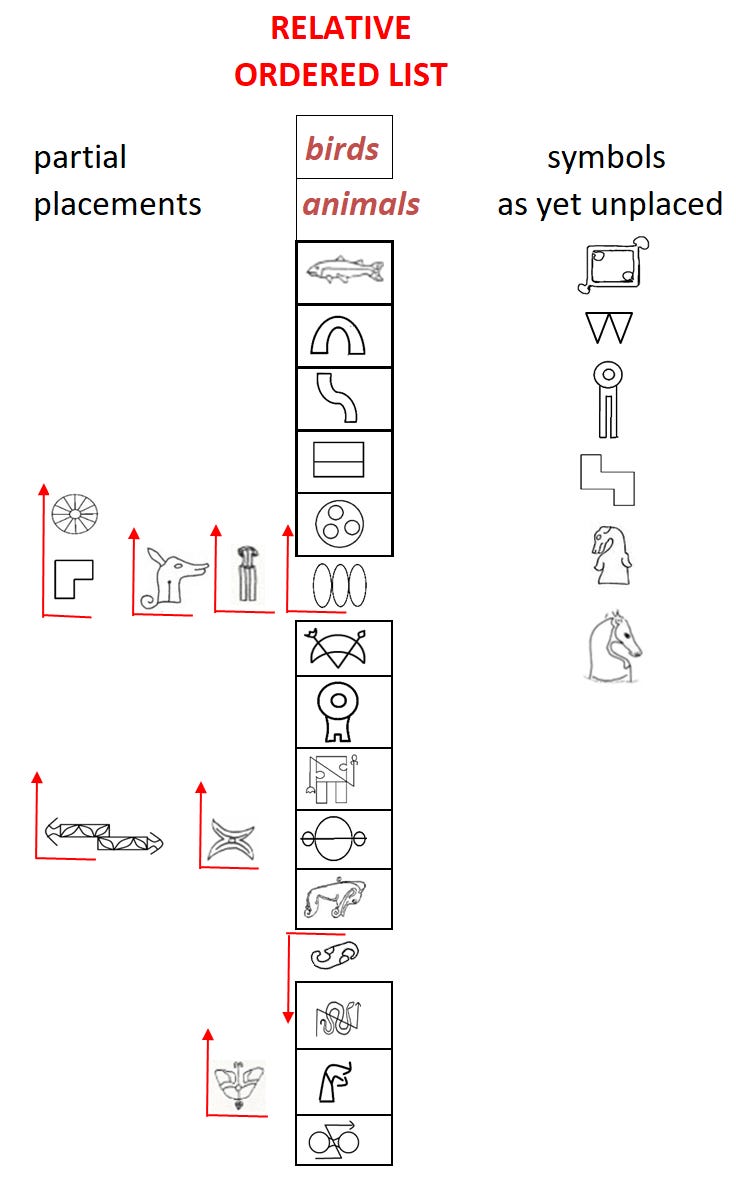

Symbols usually occur in a pair, and are sometimes accompanied by a mirror, or a mirror+comb, as modifying symbols. A pair of symbols without a mirror+/-comb usually is depicted in a given order. For example, the crescent/V usually sits above the double-disc/Z. By taking the order of pairs and combining them, it is possible to reverse-engineer a list of the symbols in their relative order. By relative order is meant that we can tell that the crescent/V sits above the double-disc/Z in the ordered list, but we can’t always tell how many other symbols might be located between those two symbols.

If a symbol stone’s pair is in the same relative order as the ordered list, the order is here termed ‘normal’, if back to front it is termed ‘reverse’.

For the common symbols, the relative order can be fairly well established. For demonstration purposes, here is a selection of symbol stones showing how a relative order can be established. All stones with a known status of definitely not having a mirror+/-comb were used to verify placements.

Not all symbols can be assigned a place in the list at this point, simply because there isn’t enough data to place the less frequent symbols. The following list is as far as I can take it at the moment, but hopefully there will be more data available as more stones are found.

Symbols which can be assigned a definite place in the ordered list have been outlined in a box. Any other symbols are only likely places given other factors.

It’s really important here to understand that all the symbols shown here in the ordered list have a relative placement. For example, it is certain that the arch symbol sits above the ogee symbol in the list, but we can’t be sure of the number of symbols, if any, that might yet occur between those two symbols.

Most of the frequent symbols appear to sit at the bottom of the list, with the double-disc/Z the last symbol that can be identified. (In fact, it was the strange placement of the double-disc/Z symbol in its pairings that first alerted me to some sort of order being applied to the symbol pairs.)

Positioning the less frequent symbols

For the less common symbols we can often only determine a partial position, for example, we might only be able to say it occurs ‘above the crescent/V’, or ‘below the cauldron’. These are marked with red arrows in Fig. 2, for instance the double-crescent is above the Pictish beast symbol but precisely whereabouts in the list above cannot be determined at this point.

Most of the less frequent symbols, including most animals and birds, seem to be placed in the upper portion of the symbol list.

It is also difficult with a number of rarer symbols to clearly tell whether they are odd variations of known symbols, or completely different symbols.

A number of symbols could be a variation on one symbol, or separate symbols, but their status cannot at this point be identified. For example, there are questions over the group – rectangle, small-rectangle, stepped-rectangle, double-stepped rectangle, and the Monymusk symbol. All we can do at this stage is hope that discovering the meaning of the symbols will eventually clarify these relationships.

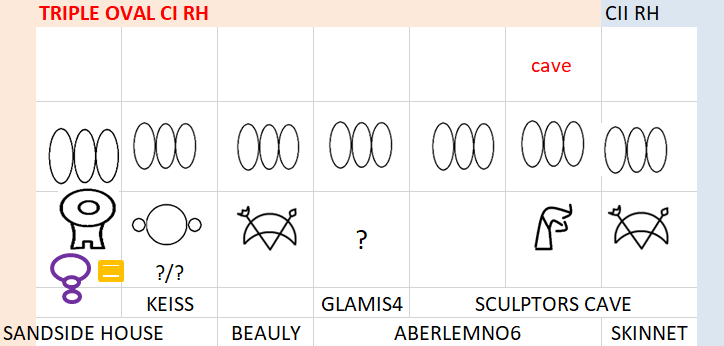

One thing though that does give some guidance, is that symbols tend to prefer to pair with other symbols in their own part of the list. So for example I have given a possible placement (unboxed) to the triple-oval symbol just above the crescent/V, as the triple-oval occurs with both the crescent/V and the disc-over-rectangle symbols. The triple-oval symbol also occurs over the cauldron and flower symbols also in the lower part of the list. Despite this likely placement, it’s still possible the place of the triple-oval could be at some other position in the list above the crescent/V.

There is more information held by those symbols with a mirror+comb, which haven’t so far been used in this analysis. Most of these pairs with a mirror+comb occur in the normal order, but a select few are in reverse order, so they cannot be completely relied upon to build the ordered list.

The animals and birds

Apart from the snake/Z and the Pictish beast which are frequent symbols in the lower part of the list, all the animals and birds seem to occur in the upper portion of the ordered list.

The birds appear to occur over the animals. But beyond that, the animals occur together in a pair too infrequently to be able to refine the order.

However, there are a few abstract symbols which occur above the birds and animals, but too few examples to be sure these aren’t just peculiarities. It may even be that the birds and animals are groups which have no assigned place in the list, but can be placed with an abstract symbol randomly – although this seems unlikely given the strict ordering and other syntax we are observing.

It is a distinct possibility that the ordered list is actually a matrix, with two or more abstract columns of symbols, and one or more columns of birds and animals inbetween these two rows.

Alternatively, it may be that the birds and animals are each a part of an abstract symbol and are assigned the same place as their abstract symbol, although again, this feels unlikely.

In Fig. 4 below I’ve made one possible version of this matrix. The problem is though that with so many symbols unable to be safely identified or safely placed, the possible versions of such a matrix are many. I’m not suggesting that this offered version is even a good candidate for the matrix, I am just presenting it as an example of how such a matrix might look.

If we have a matrix of symbols, this will inevitably mean that symbols across its rows are also going to be connected in meaning, which will eventually assist in discovering the meaning of the symbols. So when assigning possibly places in the first column, I have tried to use these cross connections, again assuming that symbols close to each other tend to prefer to pair with each other.

How many symbols are there?

If the symbols come from an ordered list which has a defined structure and therefore limits, then a key question to ask is how big is this list or matrix? How many symbols in total are there?

One problem we have is that it is still difficult to even know precisely how to define what each separate symbol is? For instance, is the Monymusk symbol a version of a stepped-rectangle, a version of the ‘sword’, or another symbol entirely? Without a number of examples, it’s impossible to say at this point.

Should we only count as ‘real’ symbols, those which occur as one of a pair? We can’t say for sure, as we don’t understand the function of stones and symbols. Valid single symbols are found on small pebbles in Shetland. Is the Burghead bull a valid symbol from the symbol set, but found alone because it is performing a different function at Burghead? Or is it just an icon not otherwise present in the list? (To be safe, I’ve only used a symbol from a pair in the below graphs.)

The symbols were not created for use on a symbol stone, their meaning individually and as a set belongs to a wider cultural context. So there may be many symbols that simply aren’t relevant for use on a symbol stone at all. Which may mean we’re only seeing a subset of symbols.

Another problem is that a few symbols are quite frequent, but the frequencies of the rest of the symbols drop off very quickly (see charts below), leaving the bulk of symbols with very small representative samples. A graph of this type of usage tells us that the tail end of this graph could go on for quite a long way, meaning there is an unknown but possibly large number of symbols we just haven’t found on a symbol stone so far.

A related question is, how many original stones are now lost? If we say, for argument’s sake, that the loss is 50%, then there may have originally been another half dozen or so symbols only used once on the lost stones.

In the end, there is no easy answer to this question of how many symbols there are in the ordered list. We currently have at least 30 plus, but the actual number could be many more.

If I had to take a guess, it might be a total of 60. Why? Because this number crops up in all sorts of contexts in Celtic cultures and their precedents, it’s a very powerful number which can be divided in many ways – 60 stones in the Ring of Brodgar, 60 months in the Celtic calendar. The number 30 too is a factor of 60, frequently found used as an ‘age’ or ‘generation’.

The research process

This research was quite difficult, well it still is, for a number of reasons. The first is that the stones are often eroded, trimmed off, or broken, so it’s not always clear exactly what the full setup on a stone is. This is especially difficult for the small comb, often drawn near the edge of a stone and easily lost. But unless I could establish whether it’s positively the case that a symbol stone has no mirror+/-comb, I couldn’t use it in this analysis. While there are now just over 200 symbol pairs known, the set that can be used to determine the symbol order is only about a third of this number, and 40% of those only use the three most frequent symbols. Which leaves the body of useable data very small indeed.

How I first noticed that something was non-random about the order of the symbols was with the list of double-disc/Z symbols, the symbol which sits at the bottom of the list. For CI symbol pairs without a mirror+/-comb, the double-disc/Z always sat as the lower symbol. However, when a mirror+/-comb was present, this symbol could move to the upper position. And at this point it was also quite evident that things changed in the CII group. Which is why I chose initially to do this analysis only with CI symbol pairs that could be definitely identified as having no mirror+/-comb.

Standardisation While I am calling these findings the ‘rules’ of symbol syntax, it’s possible that the Picts did not see these rules as absolute, in the way modern standardised rules are rigourously applied. No matter how hard I try, for every rule there is one or two exceptions. That’s not a lot in a body of just over 200 symbol pairs, but eventually the exceptions do need an explanation.

Face To begin with, I didn’t know where to draw the line between what may be one symbol and another (in a few cases I still don’t). Were the LH and RH versions the same symbol, or did they sit in the same place in the ordered list – eventually I could see the answer was yes, they are just two faces of the same symbol, so these data sets could be combined.

Rods and no rods Were the symbols with a rod a separate symbol to the ones without a rod? That has given me a headache for many years, and although I now know that the symbol with a rod is essentially the same symbol as the one with the rod, I’m still not totally sure if they are treated on the list as the same or separate symbols! But initially I held them as separate. (I will discuss more on this topic in the blog about symbols without rods.)

Mirror alone These stones were exempt from the initial analysis, however it quickly become obvious that the mirror reversed the normal order of the symbols, and so these pairs could be added back into the analysis.

Mirror+comb About 20% of CI symbol pairs are accompanied by a mirror+comb. These stones aren’t a minor part of the body of symbol stones, but they’re also not the main group. In this research, I simply left these out. It turned out that most of the symbol pairs with a mirror+comb are in the correct order, but there are a few in the reverse order, so this information can only be used with caution.

Determining what is a separate symbol Then there is another problem – some of the symbols are difficult to tell where they belong, for example, is the symbol on the Strathmiglo stone a ‘disc-over-notched-rectangle’ with extra long legs, or it is a ‘sword’ with a different head, or an entirely different symbol? When in doubt, I either left these symbols out of the initial analysis or kept them as separate symbols.

Distance As time went on, I also realised that symbols that occur near each other in the list tend to like to be together in a pair, which is the basis on which I’ve assigned some possible positions (unboxed) to some of the rarer symbols when I only have a partial order available.

Checking for exceptions

Lastly, we need to test this re-engineered order as it stands by looking for any stones which have symbols in the incorrect order (as I’ve identified so far), without any modifying mirror+/-comb. While most of the 202 available symbol pairs conform to the symbol order when not accompanied by a mirror+comb, there are a few symbol stones which do not, although there may be others with rare symbols that have not so far been assigned a position.

The two Logie Elphinstone stones both have symbol pairs in the ‘wrong’ order, and a third shows evidence of being a practice piece. All were found lying together in one spot, suggestive that we may have a location for stone carving practice, not valid symbol stones.

The only two fully validated symbol stones with the incorrect order not accompanied by a mirror+comb are Crichie and Clynekirkton1. Oddly, although most stones with a mirror+comb have a normal order, the Keith Hall stone, again with reverse order symbols, was found near the Crichie stone, so this reversal of symbols may have something to do with the location itself.

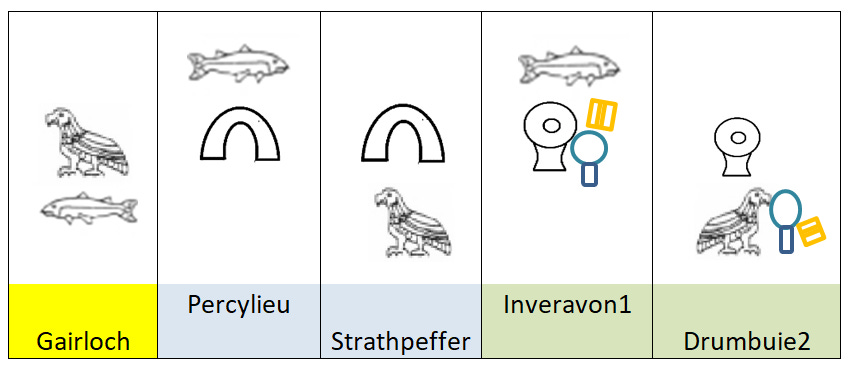

One of Percylieu, Strathpeffer or Gairloch will also be ‘wrong’, but as I can’t clearly identify the position of the arch or the disc-over-rectangle, I cannot as yet tell which stone is ‘wrong’, just that one of them must be. As most stones with a mirror+comb are in the normal order, the Drumbuie2 and Inveravon1 stone (in green), if both are in the correct order, are confirming the correctness of Strathpeffer and Percylieu (in blue), making Gairloch the odd one out with a reverse order. But if this is correct, that the salmon sits above the arch in the first column of the matrix of symbols, this may indicate it is possibly one of, if not the, first symbols in the entire list. However, another solution may be that Percylieu is incorrect and Inveravon1 is in reverse. This is an example of how difficult this assignment of position is for many symbols with so little good clear data to go on.

This gives a total of only three CI stones that I am aware of that do not conform to the rule of order, although there may be more in the group of infrequent symbols. Why these stones have the ‘wrong’ order isn’t clear, except that they are an exception to the rule. And perhaps we shouldn’t expect the Picts to rigidly follow rules in all cases, as we expect of modern standards. Alternatively, the order of the symbols may be a secondary effect caused by another outside factor, which happens to play out differently in just these exceptional cases.

The implications of an ordered set of symbols

The discovery that the symbols come from an ordered list of symbols has several critically important implications for the study of the symbols.

First, it shows that the symbols are part of a discrete and limited set with internal structure, and that this has always been the case. This is the reason why the body of symbols used remains constant through possibly over 800 years of stone carving.

The fact that the symbols aren’t just a limited set, but an ordered set, implies that the set as a whole has some structured meaning to it. And this is the best thing to discover, because it gives us hope that we will eventually find the key to unlocking the systematic structure of the list as a whole, and so be able to test how the meanings of individual symbols then fit within that connected and structured system.

Adding a new symbol

The implication of an ordered set of symbols is that the group as a whole has connected and integrated meaning organised across the entire list. And this would presumably made it hard or impossible to add a new symbol – there is no place to insert a new symbol without upsetting the balance of meaning and connection.

As can be seen from the above charts of symbol frequency, there are more symbols (30 plus) used on Class I stones than Class II (20 plus). And there is nothing to indicate that there hasn’t been a wide range of symbols used on Class I stones from the beginning. If anything, symbol usage becomes more constrained as time goes on, not less.

Implications for dating the symbols

The symbols stones, and even the pairs of symbols in caves, right from the start of Class I stones, display the rules governing order. In fact, as I’ll discuss in the next parts of this series on syntax, the rules governing the symbol configuration on stones and the use of the mirror and comb, all these aspects of symbol syntax are present from the start of the symbol stone tradition.

What this implies is that the symbols themselves, and the ordered symbol set, along with the syntax rules, are much older again than the stone-carving tradition which likely was taken up in Britain under Romano-Celtic influence. Such a large body of work to establish and agree on the concepts and structure underlying the symbol set must of necessity come from a long tradition of scholarship. This pushes the dating of the symbols themselves (not the symbol stones) back at least into the late centuries BC.

The next steps

Once we have a basic outline of the ordered set of symbols, the next thing to analyse is how and why this order can be changed on a stone. First, I’ll look at the mirror, and then the mirror+comb, and finally the context in which a symbol loses its rod.

Great to see this painstaking work being presented so clearly at last after what I know has been years of work. Really fascinating to think about what could be going on behind this ordering.

And this is the single strongest argument I know *against* names. For them to be X child of Y names, the parent/child roles would have to be implicit by order. If the order is set, they really can't be personal names.

I had thought for a while they might be times of year, and the mirror still made sense with this (instead of saying Feb to March, a one month span, you might need to indicate March to Feb, an 11 month span) but with the most frequent symbols clustered at the bottom, this too makes less sense as important dates in the year would be spread through the calendar.

If they relate to features in the landscape, as you've alluded to elsewhere, then I'm not sure why they'd _need_ an order, but perhaps that's looking at it backwards. Perhaps there having already been established a proper order to key elements of the world, it is only proper when referring to them, to refer to them in order except when reversals "need" to be made and indicated.

I look forward to seeing more!

Fantastic work here, Helen. The "symbols tend to prefer to pair with other symbols in their own part of the list" aspect sounds interesting and promising. I presume with the animals and birds it's not as simple as birds above animals above fish to represent sky, earth and water?