WHAT LED TO THE BATTLE OF DUN NECHTAIN?

Exploring the idea that the fear of plague lay behind Ecgfrith of Northumbria attacking Pictland in AD 685.

King Ecgfrith of Northumbia led his men on a precipitous foray into Pictland and he was killed by the Pictish king Brude mac Bile on 20 May AD 685 at the Battle of Dun Nechtain. He had been advised against this raid by his councillors, and was soundly condemned after it. But no one today knows why Ecgfrith did this.

But the answer may be fairly obvious. A clue to the answer may lie in the DATE. And in this blog, I will be exploring what that date meant for Ecgfrith and Brude and their peoples.

I will largely be using textual evidence and ideas that have already been floated in academic circles, but I will be using this evidence to paint a different story behind Egfrith’s actions.

PREVIOUS IDEAS

Researchers have of course asked this question of Ecgfrith’s motives for the raid into Pictland many times before. The problem has been that while the battle itself and the reactions of people to the battle were written down for us, none of these early writers told us why Ecgfrith attacked Pictland.

One proposal that has been favoured is that Ecgfrith attacked Pictland to re-assert his waning power over the Picts[1]. The Picts had been under subjugation to Northumbria from the reign of Oswald of Northumbria in the 640s, that is for 45 years before the Battle of Dun Nechtain. This idea that the Picts were pushing back against the Northumbrians prior to the battle in 685, largely rests on an assumption that the Picts were regaining power under their king Brude (reigned 671 to 692). The sieges of Dundurn and Dunottar are generally attributed to Brude today, although the annals don’t tell us who was involved or who won. So, while we can conjecture, this may be a case of hindsight bias, for there is no written or archaeological evidence to confirm this idea.

But there is one good reason to find the idea unsatisfactory. If the Picts as a tributary people had been pushing back against their Northumbrian overlords, the Northumbrian elites and clerics would not have been averse to Ecgfrith doing what was his duty to do – maintaining his kingdom and its power over its neighbours. Instead, we see them adamantly and loudly decrying his vicious aggression, and attributing his death to the righteous vengeance of God.

This was a period of rising insular kingdoms, clashing against each other, kings made into saints for their battle leadership in the struggle for power over their neighbours. Most kings of this century died in battle - it was the rule rather than the exception. Ecgfrith’s grandfather Oswald has a story almost parallel to Ecgfrith’s. Oswald, aged 38, died in the battle of Maserfield against Penda of Mercia, a war in which Oswald was the aggressor. Before the battle Oswald claimed a vision in which Saint Columba urged him to ‘Be bold and manly’[2]. And Bede records that he died ‘in prayer’[3]. Oswald was never vilified by his own people, to the contrary he was praised and venerated as their patron saint. How different then is the picture of the veneration of aggressive Oswald attacking his neighbouring kingdom and dying in doing so, to the picture of Ecgfrith, the king who led his army ‘to ravage the province of the Picts’ and was utterly condemned for it. That these two similar events were viewed so differently suggests the motivation behind Ecgfrith’s actions was unusual and not judged as appropriate by his contemporaries.

Had the Picts been causing concern by uprising against Northumbria, we’d expect Ecgfrith to have been praised for his leadership in attacking the Picts, and the Picts would have been denigrated as the enemy, the trouble-makers. Yet, that’s not how Bede describes the situation, he makes no mention of any wrong-doing by the Picts, nor does he say Ecgfrith had gone to wage war on the Pictish king, instead he says that Ecgfrith ‘devastated their territories with most atrocious cruelty’.

I think with this contemporary evidence for Ecgfrith’s actions, we should be wary of the idea that he was attempting to re-assert his control in a targeted war against a rebellious tributary king, which he would have been considered within his right to do. His actions sound more like a vicious smash and grab raid.

But why would he do such a thing?

THE RAID ON BREGA IN THE PREVIOUS YEAR

Actually, this wasn’t the first time Ecgfrith had done such a thing. The year before, in 684, he had sent his army across the sea to Brega, a region in the mid-east of Ireland, where with ‘hostile rage’ they ‘lay waste Mag Breg, and many churches, in the month of June’[4]. The raid was devastating, smashing churches and monasteries, and taking 60 slaves. The insular world was horrified that this Christian king, founder and supporter of Northumbrian monasteries at their height, would commit such a heinous act against the church.

At this point, it is worth reading the full section from Bede[5] to gain a feeling of just how outraged he was about the Brega raid, and to see how he directly attributed Ecgfrith’s death to the vengeance of God for the raid.

In the year of our Lord's incarnation 684, Egfrid, king of the Northumbrians, sending Beort, his general, with an army, into Ireland, miserably wasted that harmless nation, which had always been most friendly to the English; insomuch that in their hostile rage they spared not even the churches or monasteries. Those islanders , to the utmost of their power, repelled force with force, and imploring the assistance of the Divine mercy, prayed long and fervently for vengeance and though such as curse cannot possess the kingdom of God, it is believed, that those who were justly cursed on account of their impiety, did soon suffer the penalty of their guilt from the avenging hand of God; for the very next year, that same king, rashly leading his army to ravage the province of the Picts, much against the advice of his friends, and particularly of Cuthbert, of blessed memory, who had been lately ordained bishop, the enemy made show as if they fled, and the king was drawn into the straits of inaccessible mountains, and slain with the greatest part of his forces, on the 20th of May, in the fortieth year of his age, and the fifteenth of his reign. His friends, as has been said, advised him not to engage in this war; but he having the year before refused to listen to the most reverend father, Egbert, advising him not to attack the Scots [the Irish], who did him no harm, it was laid upon him as a punishment for his sin, that he should not now regard those who would have prevented his death.

The Venerable Bede wasn’t the only one linking Ecgfrith’s death to righteous vengeance for the Brega raid. A poem attributed to the Irish monk Riaguil of Bennchor[6] has the same message, told from an Irish perspective. (This is an updated translation of the poem I did with the help of the Old-Irish-L linguists, with particular thanks to Prof David Stifter.)

Iniu feras Bruide cath, im forba a senathar Manad algas la mac De, conide ad genather Iniu ro bith mac Ossa a ccath fria claidhme glasa Cia do rada aitrige, is hi ind hi iar nassa Iniu ro bith mac Ossa, las ambidis duba deoga Ro cuala Crist ar n-guidhe roisaorbut Bruide bregha Today Bruide makes battle for the patrimony of his grandfather Unless the son of God does not wish it, tis he who will make reparation [for Ecgfrith’s attack on Brega] Today mac Ossa [Ecgfrith s. Oswiu] has been slain in battle against blue swords Although penance was said, it was penance too late Today mac Ossa has been slain, whose drinks were black Christ has heard our prayers, Bruide has freed Brega [of obligations].

So now we have two mysteries, two questions to answer. Why did Ecgfrith attack the churches of Brega in 684 with hostile rage? And, why did he attack Pictland in 685?

As Bede uses much the same language to describe both the Brega and Pictish raids, linking them in the same paragraph, it raises the distinct possibility that Ecgfrith was also intent on destroying Pictish churches, just as had been done in Brega. But if so, this would make his actions seem even more out of the norm, more deplorable.

Brega is a fertile, well-populated region, and has long been a symbolic centre of ritual and religion and power, both pagan and Christian, encompassing as it does the complex of ritual sites in Meath, Tara, Knowth, Newgrange and so on. By the time of the raid, Brega also had several significant Christian churches and monasteries, including Monasterboice, Rechru, Durrow, and Terminfechin, and in the Viking era, the Ionan church would establish Kells as an inland refuge.

Again, researchers have asked the question why Ecgfrith would have ordered such a devastating and shocking raid on Brega? A tentative suggestion has focused on Fínsnechta, the Irish king of Brega and High King of Tara. Fínsnechta certainly was a busy battle king of significant power in his day, but there is no mention of any battle between the two groups. Fínsnechta also has stories told of him in which Adomnan of Iona is acting as his principal saint and advisor.[7] Adomnan would be the person who later journeyed to the Northumbrian court to negotiate the release of the Brega captives, two years after Ecgfrith’s death[8]. But a regional power that was connected to Iona was common enough, so that alone hardly seems to warrant a risky attack.

Another suggestion is that Ecgfrith was raiding the Irish monasteries for their wealth and slaves, so as to give them to his own supporters in return for their service[9], much as the Vikings would later do. I think it’s hard to accept this idea, when Ecgfrith already had control of large regions and monasteries with fast-growing wealth, why he would risk a raid in a far-off place, against Christian churches, and under the nose of a powerful Irish king. I feel sure he had ready access to plenty of alternative avenues of wealth. But, this idea does demonstrate just how difficult it has been to come up with a clear reason behind Ecgfrith’s behaviour.

There is one mention in the Annals of Clonmacnois of the ravaging of the plain of Brega because of an alliance between the Irish and the Britons, but it makes no mention of how this alliance related to either Northumbria or the Picts. This has led to scholars attempting to propose a cascade of odd inter-kingdom relationships which may have led to Ecgfrith taking umbrage in some unknown way to an unknown alliance between other parties[10]. But the strange thing here is that this was not a battle with another king, nor a siege of a stronghold, this was a rage-filled, large-scale ‘ravaging’ with no political motive or outcome that is recorded. Indeed Bede explicitly says that the people of Brega were ‘harmless’ and twice asserts they were ‘most friendly’ to the English, a statement that confounds any modern proposal to claim this was an attack on an enemy, or a treacherous ally.

It’s difficult to go past the suspicion that the Brega raid was not targeted at Fínsnechta, or the Ionan church, but rather their goal was to do what they actually did – a devastating destruction of the churches of Brega.

Which leads me to ask again, why on earth would Ecgfrith do so? What could be so dire that, against the advice of his clergy, he would risk an infamous act that he must have known would be considered so heinous and sinful? And, why would he perhaps have repeated it the following year in Pictland with ‘atrocious cruelty’, again against the explicit entreaty of his churchmen? Up to this last year of his reign, Ecgfrith had been a successful king, ruling over a powerful and flourishing kingdom. He had managed to negotiate his way through inter-church rivalries that make your head swim. He had lost a few battles, but he’d also won a lot, and not gotten himself killed in doing so. His sudden change of behaviour in ravaging Brega and Pictland was a distinct change that needs an explanation.

People don’t do dreadful things in a vacuum, they act out of many impulses, and one big motivator is fear. But to see why terror may lie behind Ecgfrith’s actions, we need to go back twenty years, to the year he was nineteen. The year that his world shattered.

THE YEAR AD 664 : ECLIPSE, SYNOD, PLAGUE

The year 664 was momentous. Momentous in a good way for some, but mostly momentous in the worst way possible.

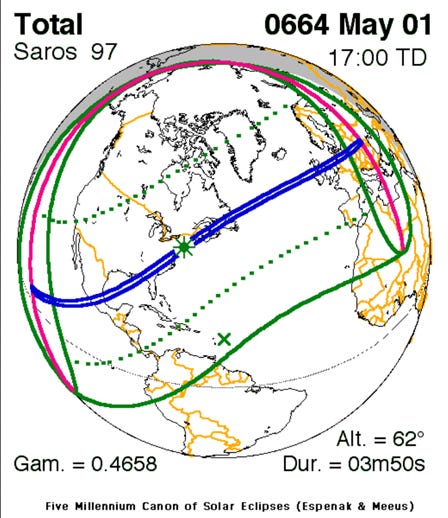

To start with, there was a full solar eclipse on May 1.

An eclipse was ominous enough, what dire events might it presage? But to occur on May 1, that must have rocked the insular world. For millennia, May 1, Beltaine, was considered the beginning of the year[11] (as displayed on the Coligny calendar), and, the beginning of a new era of history. A solar eclipse on May 1 would have been perceived as a very clear message – the world was starting a new age, things were about to undergo a massive change.

In mythology, we see this change of era for instance, as the Tuatha De Danann arrive in Ireland on May 1. Another instance that always makes me smile is Columba arriving on Iona on May 1, a clear statement that he brought with him the new era of Christianity. Did he really do this, or is it just a story with a message? I suspect it’s entirely possible he deliberately chose this day precisely because of its significance.

That same summer of 664 saw churchmen gather from Ireland and Britain for the Synod of Whitby, a synod which would go down in history. At stake were a few key points of disagreement between various church factions, including the way a monk should wear his hair, and the astronomical method for calculating Easter. Now these matters today may seem laughably trivial, but these arguments were fierce and deeply felt, and had been going on in various ways for centuries all over the Christian world, faction against rival faction. This wasn’t really about astronomy, the Romans had seen to that by disregarding that science to the point where neither the Celtic nor the Greek mathematics of astronomy was any longer taught or understood. This Easter debate was an excuse, propaganda disguising power struggles to see which church group could gain ascendancy over its rival. In the case of the Synod of Whitby, the Columban familia lost out in the argument with a rival British group claiming – falsely – to be aligned with the Roman tradition. Intriguingly, the person who decided this Whitby debate for once wasn’t a cleric himself, for clerics had spent centuries showing themselves completely incapable of giving way to a rival group to resolve this argument, no, it was the king himself, Oswiu, Ecgfrith’s father.

The synod didn’t end the dispute though, it merely made one group more powerful than the other. The intensity of this division would ripple down through many years to come, the Ionan church no longer in ascendancy in Northumbria despite it being so intimately involved in the founding of Northumbrian churches. Nor did it necessarily convert people’s beliefs to the opposite view point, Iona itself struggled for years to convert to the ‘Roman’ method, and one can only imagine the emotional turmoil of the losing side. Even amongst the Northumbrian churches not everyone agreed with the decision, some feeling so deeply that they relocated to Ireland to avoid changing. The important thing to note here, is the division and intensity felt by all about these matters in both Oswiu and Ecgfrith’s days.

Bede went to great length to write down the debates verbatim, for posterity to read, he considered these matters so critical. We might think that was a straightforward case of correctness for him, but life was suddenly to get far more complex, ambiguous, unstable, uncertain, an event that would throw a shadow of doubt over everything.

For the third momentous event of 664 was now to knock their world asunder. Shortly after the eclipse, and the synod, as Bede starkly wrote: ‘And the pestilence came.‘ One of the worst waves of the bubonic plague to ever roll across the world.

This wave would cause death on a scale that is unthinkable, the death notices in the annals of kings and bishops attest to that. Tuda, appointed bishop of the Northumbrians after the synod, was struck down. Amongst the list of dead were Cedd, bishop of the East Saxons, and all 30 of his monks save one small boy, gathered around the shrine of their saint, vainly praying for safety. Saint Cuthbert would be one of the few who miraculously recovered while most of Lindisfarne’s monks died[12]. Ripon, Ely, Gilling, Melrose, Jarrow, Barking, Lichfield, Lindisfarne, Wearmouth, the plague continued to randomly ravage the monasteries for 16 long terrifying years, killing the religious of one church after another. Ecgfrith’s first wife, Aethelthryth, lay among the dead, three days after having her ‘tumour’ lanced in an effort to save her life. Ecgfrith’s eldest brother Alhfrith, who had been a key proponent of the ‘Roman’ method at Whitby, disappears from the records in the same year 664, another likely family victim of the plague[13]. The list of dead in Ireland reads like a who’s who[14], one dead after another. In a world where plague was routinely viewed as reflecting God’s anger, the devastation of the monasteries and their rulers coming so close on the decision made by the synod, must surely have raised concerns that the decision had been wrong, that it had displeased God.

To make matters worse, the Ionan church, the principal ‘loser’ of the Whitby debate, claimed that the Dal Riatans and the Picts remained free of plague, under the protection of their saint, Columba[15]. If true, or even if claimed to be true, this protection of God through his Ionan church, will surely not have passed notice, a stark contrast perhaps as an indication of God’s view on the Whitby decision.

I’m not alone in thinking that God’s displeasure in sending the plague was likely linked to the Synod of Whitby’s decision being wrong. David Woods summarised his article on this topic[16]:

Adomnán does not seem to have believed that he had to look far to discover why God had spared the Picts and Irish in Britain alone when he had struck Britain, Ireland and the rest of western Europe with two great epidemics of plague c. 664 and c. 684. The coincidences in timing and geography pointed firmly in one direction: he had done so in order to reward them for their continued use of the right Easter table while he punished all the other peoples for their use of the wrong Easter table.

We’ve just lived through a 3-year pandemic that had a death rate of around 3 in every 100. Estimates of the death rate in 664 vary between 70 to 90 in every 100, and this wave would last in smaller outbreaks for 16 years. Northumbria may have even suffered outbreaks of the pneumonic version of plague with a kill rate of close to 100 per cent, as we hear at Lindisfarne the plague started in winter at Christmas and continued through the cold months for a whole year[17]. Plague kills a person within a day or three, it is sudden, random, unstoppable, people then knew no cause, and no cure. We must not underestimate the abject, helpless terror that the plague instilled in the hearts of victims and survivors.

The Justinian plague had started in the mid 500s, and it continued with outbreaks in small and large waves for the next two hundred years. Stories that were recorded still shock, the mother sitting wordlessly insane by her dead child’s bedside, survivors wandering in a stunned daze till they dropped and died from shock, the man who has lost his wife and children between dawn and dusk, scattered corpses left to rot with no-one strong enough to bury them, corpses shoved by their thousands into the city walls until the stench made the city unliveable.

With no known cause or cure, the church had to find a way to explain the devastation, why so many were dying, including the innocent children. They did this by saying that God had sent the plague as a dire warning to all people to keep to the path of righteousness and to stop their sinning. This one message is documented by writers all over the Christian world, with one notable exception, the Venerable Bede.

Bede does repeat the assertion of Gildas that the earlier mid 500s wave was divine punishment for the sins of the Britons. But on the major plague starting in 664 which Bede witnessed himself as a 15-year old, he strangely pulls back. He admits that the plague is ‘a blow sent by God the creator’, but does not focus that on the sins of a more specific target, unlike his contemporaries. It is thought that this was because he lived in Northumbria which in this century had seen the ‘happy’ establishment and flowering of Christianity with its churches and monasteries, which surely could only have been pleasing to God[18]. There is another possibility to consider though. All three events, the eclipse, the synod decision, and the simultaneous outbreak of virulent plague with so much death visited on the Northumbrian churches, may well have been viewed as linked together in cause and effect, because these types of beliefs were prevalent in the day, attempting to make logical sense of fickle fate. Even if Bede himself did not hold the view that the plague was God’s justice for an incorrect decision at Whitby, he may have avoided the topic as being too vulnerable to a suggestion that a wrong decision had been made. Things had become too chaotically uncertain.

Monasteries were undoubtedly implicated in the transmission of plague[19]. The ‘number and contiguity of their residents’ made monasteries Petrie dishes for infections to fester and explosively spread. Exponential expansion loves proximity. The outbreak of plague is recorded with the first deaths in July 664, nearly simultaneously in south and north England, and in Ireland by August 1. This extraordinarily fast spread of the plague in 664 was likely facilitated by movement between monasteries, being hubs of population and trade. It is even a distinct possibility that the gathering of so many monks traveling to the synod had in fact brought the plague with them and taken it with them as they left. The alternative, that ships from Gaul arrived with the plague at all ports at the same time, seems unlikely as the progress of later plagues has shown such scenarios to have a much slower rate of spread. In all, there were plenty of reasons to be concerned about the role of churches in the propagation of the plague, to say nothing of their vulnerability to mass casualties.

Irish records tell a different story about the plague of 664[20]. The story goes that the Irish king thought that the population had undergone such an expansion that it would inevitably lead to widespread famine and death – which it actually did cyclically. So he asked all the major saints of Ireland to bring down the plague to reduce the overpopulation. Most denied the request, but a handful agreed, they fasted against God and in response to the criticism he sent the plague. One of these saints was Fechin of Fore, who himself would die in the plague[21].

It may also be relevant that the outbreak of plague in Ireland is reported on a specific date, August 1, Lughnasad[22]. Great gatherings of people from far and wide were held at this time, in particular at Tailtiu, in Brega. So it is possible that this gathering did indeed cause wide and sudden transmission, just as we’ve recently witnessed gatherings do during covid.

So, the Northumbrians had available to them a story that the Irish church were implicit in causing the plague in 664, and perhaps another that a pagan festival was responsible. They were also hearing a claim that the Ionan church was being protected by God from the plague. Added to this was a coincidental link between the eclipse on an auspicious date, the synod’s decision, and the outbreak of plague in Northumbria, which may have been suspected as God’s judgement on a wrong decision by the synod.

Ecgfrith, as a nineteen-year old in 664, lived through these chaotic, terror-filled, uncertain, grief-stricken, often hopeless days that followed the Synod of Whitby. He had watched so many people around him die suddenly, inexplicably, in agony. He would not forget. Nor would his people.

The major wave of 664 continued in local outbreaks till about 680, when it waned for a few years. But, experience told them to expect another outbreak. It was just a question of when, and what would trigger it.

STOPPING THE PLAGUE : THE BREGA DEVASTATION of 684

Twenty years after 664, we come back to 684, the year of the Brega raid. The year that the next major wave of plague broke out.

Just as in 664, an eclipse had occurred on May 2 of the previous year. Although partial this time, it still would have caused trepidation of what was to come, given what had happened last time. And as if to confirm this worry, in the same year a major disease killed ‘all animals in common, throughout the world, to the end of three years, so that scarce one survived in the thousand of every kind of beasts’.[23]

In Ireland, several annals for 683 noted a children’s plague which would last for three years. The next year, 684, we have recorded ‘The plague of youths, in which all the chieftains and nearly all the young Irish noblemen perished’. While we can’t be certain that this plague of children was the bubonic plague, it is more than likely[24]. Larger waves of plague tended to happen when a new generation had been born without any immunity from previous exposure, making these later waves killers of children and ever more devastating.

Imagine the concern of everyone in Britain and Ireland, standing, waiting, watching, for the plague to arrive at their own place. Well, a lot of people didn’t stand and wait, they fled. They fled in terror to the farthest places they could get to. Inevitably, unfortunately, taking the plague with them. In Muslim countries, fleeing was made a capital offense, flee and we’ll kill you. In Ireland, we have a description of the Irish inlets thick with boats (presumably refugees from the continent) while the king Diarmait, in great fear of the plague, plead with saint Ultan to raise his hand ‘against the evil’[25].

But in 684 this was not an option for the King of Northumbria, now Ecgfrith in his prime. His role was to protect his people, however he could.

He had no science to explain the plague, no medicine to cure it, no vaccine to hope for, but he did perhaps have stories of how the Irish church was implicated in the promotion of the previous wave of plague. And he may have felt vindicated in his belief in their complicity if he thought what Adomnan reported was true, that the Dal Riatans and the Picts were exempt from the plague through the protection of Columba.

Here was something solid that he could do, he could direct his anger at the culprits. He could destroy the churches that were implicated in the spread of plague, or its non spread as the case may be. It may be no coincidence that he chose Brega to attack with ‘hostile rage’, as one of its main churches in easy reach of the coast was the monastery of Terminfeckin, the sanctuary for the ill, whose patron saint Fechin had reputedly caused the 664 plague’s outbreak. And for good measure, Brega was a region where Adomnan of Iona was the saint for the Irish high king.

STOPPING THE PLAGUE : THE PICTISH DESTRUCTION OF 685

The Brega raid unfortunately did not stop the next major wave of plague. It struck hard the following year in 685, the year Ecgfrith attacked Pictland.

We are not told that Ecgfrith’s Pictish ‘ravaging and laying waste’ was specifically targeted at Pictish churches, but the churches and monasteries were the only really obvious objectives to destroy in this period, just as the Vikings would discover a century later. It is often overlooked by historians that Ecgfrith did not just race into Pictland to meet the Pictish king in battle. Bede says explicitly that before the battle in which he lost his life, he had ‘devastated their territories with the most atrocious cruelty’.

It seems likely that Ecgfrith had tried to avert the coming plague by destruction of key Irish and Pictish churches, implicit as they were in their supposed power over the plague, which had seen their own regions protected, while Northumbria was badly hit. His targeting of churches would explain why his own churchmen had urged him against both the raids. If this scenario holds true, one of his main Pictish targets would have been St Vigeans, the church on its high mound at Arbroath, Angus, dedicated to the same plague-bringing Saint Fechin, only 10 miles from Dun Nechtain, the site of the battle. He wasn’t a king to wait at home made helpless with terror, he took what action he could.

At a time when written records were famously terse, we do find the terror of people about the coming plague leaking through. The fear and dread stand out clearly in the story of Cuthbert giving a sermon, in which he urged the monks to watch, remain stedfast in the faith, and let no temptation find them unprepared[26]. Bede in hindsight is citing this as Cuthbert having prescience about Ecgfrith’s death, but

‘some thought he said this because a pestilence had not long before afflicted them and many others with a great mortality, and that he spoke of this scourge being about to return.’

Bede then relates how Cuthbert told the story of how he had in the same way foretold the coming of the plague by urging the monks of Lindisfarne: “I beseech you, brethren, let us act cautiously and watchfully, lest, perchance, through carelessness and a sense of security, we be led into temptation.' Then, on returning to Lindisfarne the monks found that the plague had arrived as forewarned:

…they found that one of their brethren was dead of a pestilence; and the same disease increased, and raged so furiously from day to day, for months, and almost for a whole year, that the greater part of that noble assembly of spiritual fathers and brethren were sent into the presence of the Lord. Now, therefore, my brethren, watch and pray, that if any tribulation assail you, it may find you prepared.

The fear of the plague was every-present in the mind of everyone, even at the moment when their king had just been killed.

In a world of random pestilence, without cause, without cure, the only hope was the mercy of God through the intercession of his worldly saints. Ecgfrith was not alone in his belief that saints could prevent, or bring down, the plague.

Today, we, like the churchmen of his day, cannot condone or excuse Ecgfrith’s cruel destruction of the Irish and Pictish people and churches. But history is rarely a simple matter of black and white, history is hugely complex, and perhaps we can start to understand the deep, gut-wrenching terror motivating Ecgfrith to try to stop the plague before it could once again wreak its death and devastation on his own people of Northumbria.

[1] Fraser, J.E., 2009. From Caledonia to Pictland: Scotland to 795. Edinburgh University Press, p 212-216

[2] Adomnán, Life of Saint Columba (transl Richard Sharpe), Book 1, Chapter 1.

[3] Bede, Historia ecclesiastica gentis Anglorum, Book 111, Chapter 12.

[4] Annals of Ulster 685.2

[5] Bede, Prose Life of St Cuthbert, chapter 27.

[6] KBR (Royal Library of Belgium) MS 5301-20 p.30 https://www.isos.dias.ie/RLB/RLB_MS_5301_20.html#48 [7] Whitley Stokes (ed. & tr.), “The Bóroma”, Revue Celtique, 13, 1892, pp. 36–117, 299–300.

[8] Annals of Ulster AU 687.5

[9] Pelteret, David, The Land of the English Kin, Chapter 10 The Northumbrian Attack on Brega in a.d. 684, p. 214-230 https://brill.com/display/book/edcoll/9789004421899/BP000013.xml?language=en&srsltid=AfmBOop1022YCP-HedRTlKU5VP-v7mwO8SmHPm39OhJ6wrhT7oYsQjK4#ref_FN000827

[10] Higham, N. J. (2015). Ecgfrith: King of the Northumbrians, High-King of Britain, p. 207-208

[11] McKay, H.T., 2024. Identifying the Seasonal Placement of the Coligny Calendar, Etudes Celtiques, 50, pp.37-270.

[12] Maddicott, J.R., 1997, Plague in seventh-century England, in Little L.K. (ed.), 2007, Plague and the end of antiquity: the pandemic of 541-750, Cambridge University Press, p.173-174

[13] Maddicott, p.179

[14] Dooley, A., 2007. The plague and its consequences in Ireland, in Plague and the End of Antiquity, p.221-222.

[15] Life of Columba, II.46

[16] Woods, David, 2011. Adomnán, plague and the Easter controversy. Anglo-Saxon England, 40, pp.1-13. https://www.jstor.org/stable/44479625

[17] Maddicott 1997, p. 185.

[18] Maddicott 1997, p. 180-182.

[19] Maddicott, 1997, p. 188-191

[20] This story is found in the Latin Life of Saint Gerald of Mayo, and in the Liber Hymnorum for the hymn Sén Dé by Colmán of the moccu Clúasaig.

[21] This story is found in the Latin Life of Saint Gerald of Mayo, and in the Liber Hymnorum for the hymn Sén Dé by Colmán of the moccu Clúasaig.

[22] Dooley, A., 2007. The plague and its consequences in Ireland. Plague and the End of Antiquity, p.220.

[23] Annals of the Four Masters, col. I, p. 290, xz,x 684

[24] Michelle Ziegler, The Mortality of Children, Ireland 683-685 (blog) https://hefenfelth.wordpress.com/2011/10/03/the-mortality-of-children-ireland-683-685/

[25] Felire Oengusso, 198-203, in Dooley, p 225.

[26] Bede, Prose Life of Cuthbert, ch27

so - in my head - the battle of nechtansmere - a foundation stone of the formation of the scottish kingdom sometime later - was caused by the Columban church representatives staying out of the way at the synod of Whitby and not getting lice from other attendees. They lost the argument about easter dating but this separation meant that the Julian plague hit Northumbria harder than Pictland and Ireland/Scotti. The Northumbrians(Egfrith?) bore a grudge about this so - 20 years later when the plague hit again - Egfrith decided on pre-emptive strikes against first the folk in Ireland and then in Pictland! Northumbrian defeat in the latter allowed the re-development of the Pictish kingdom? Amazing really - if I haven't extrapolated too much! Pretty great though - and not seen in any other descriptions of the synod!

Thank you for sharing- that was really interesting. I'm just wondering- you mentioned that in Northumbria, it was likely to be pneumonic plague given the time of the year. Could that explain why there were so many simultaneous cases appearing in Ireland and throughout England? It would show a more rapid spread as it does not require flea bites to be transmitted. It would spread by airborne transmission and from direct contact with infected tissues or fluids. It is also the most virulent form of plague.