KNOCKANDO: LOOKING FOR A LOST SANCTUARY (2)

In which I look for traces of a sanctuary or nemeton in placenames around Knockando

In my previous blog, I looked at the spoked wheel to see what it might tell us about the example at Knockando. The spoked wheel as a symbol was also found at Ardjachie on the edge of the sanctuary of Tain in Easter Ross, the only other example apart from Knockando. We then have two chariots with spoked wheels at Meigle and Newtyle, and on the inside of a double-disc symbol at nearby Alyth, three iconographic spoked wheels at another sacred nemeton. In the Bronze Age through to the uptake of Christianity, votive spoked wheels are an ancient icon, found in their thousands at sanctuaries across Europe. Which raises the possibility that there was an ancient sanctuary at Knockando, marked with the spoked wheel symbol. A sanctuary that we have lost sight of. And if so, why would a sanctuary be here?

Here, I will search for hints of the presence of a sanctuary at Knockando.

Pulvrenan: The find location of the symbol stones

The two symbol stones and a stone with Norse runes are reported to have originally come from an old burial ground at Pulvrenan NJ 2026 4218, and moved up to the new church at Upper Knockando around 1820. The site is on the north bank overlooking a loop of the river Spey. There is now no trace of a previous church at Pulvrenan, nor is there any Christian crosses to say there ever was. But the path heads down to the river Spey, indicating the presence of a ford or ferry crossing over the river Spey, a place of danger that might require protection for travellers, the type of place we frequently find symbol stones, Christian or not.

All the stones today look to be of similar size, but the two symbol stones have at some point been trimmed down to a size which is suitable for re-use as grave covers. Their original size was quite different to each other. So it’s possible that the symbol stones were originally located elsewhere and brought to the burial ground to be re-used as gravecovers. But they would no doubt have been sourced somewhere close by, by which I mean within the general habitation area around Pulvrenan and Knockando.

The re-purposing of stones in a burial ground throws light on the Norse runes, the name of a man Siknik carved deeply and carefully on the third stone. This isn’t some random graffiti, but a burial marker of a Norseman. But, what on earth was he doing this far south? And how did Siknik die so far from home? A story of a life lost in the mists of time.

Dating the stones

The first Knockando stone with its spoked wheel doesn’t have a smoothed surface, in fact there is a fault running down the middle with a crescent/V symbol placed each side of it. This lack of prepared surface suggests this stone belongs to an early date in the Class I sequence, but just how early is otherwise hard to assess.

The surface of the second Knockando stone is fairly smoothed suggesting it has a later date in the middle of the Class I sequence, nonetheless the single-sided comb, plus the oversized ‘flower’ symbol, both indicate a fairly early date in the Class I sequence. By the time Class II stones start (exactly when we can’t yet tell for sure) only double-sided combs are depicted. These double-sided combs were introduced to Britain by the Romans, and have reached Ireland by c.300 AD, so no doubt they are in Pictland by that time too, although a conservative lag in the symbol carving tradition might be allowed for, so that some single-sided combs, like here at Knockando, could date to slightly later than 300 AD.

If I had to estimate a date here, I’d go for somewhere between 300 – to 500 AD for both these stones, but it could be earlier still.

The Norse runes on the third stone are said to be of an early type, which if correct, points to the grave, and perhaps the graveyard, being present sometime after the ninth century. But this stone too has been re-used as a grave-cover in the eighteenth century, when the name I A HAY and the date 1714 were added beneath the runes.

This dating means that we are potentially looking at anything from several centuries up to a millenium and a half between the stones being put up somewhere in the neighbourhood, then being re-used as grave-covers in the Pulvrenan graveyard. Which isn’t terribly helpful in establishing their original date and location.

In the end, all that I can say is that all three stones may originally have been set up at Pulvrenan, but they may equally have been originally located somewhere else closeby.

Ben Rinnes

The most spectacular thing about Knockando is its outlook – its southern skyline is filled by the magnificent mountain of Ben Rinnes. In a region of hills and mountains, Ben Rinnes stands out, readily identifiable by its outline, even today a great favourite for walkers and photographers. At 841 metres, Ben Rinnes isn’t all that high for a Scottish mountain, but from its summit the whole Moray coastal plain and the firth beyond can be seen.

The word Rinnes contains rind/rinn ‘point’ referring to the series of projecting granite tors on its peak, with the suffix -as meaning ‘-place’ (Peter Drummond). The mountain is a lovely round peak with projecting ‘spokes’ of granite, with lovely cascades falling down between them – viewed from above it is a giant spoked wheel in the land.

Yet language holds concepts that describe the worldview of its speakers, and the word rinn not only means ‘point’, it is also the word for stars and constellations. Ben Rinnes, the hill of the spoked wheel, the spoked wheel of the starry heavens, Ben Rinnes, the Hill of Stars.

The towering presence of Ben Rinnes makes Knockando a very special and spectacular place indeed. Even today people fill the internet with their photos. Is it possible that the symbol stones are doing much the same thing? Is the spoked wheel symbol at Knockando reflecting/’photographing’ the presence of the spoked-wheel mountain?

A centre of paths

From Pulvrenan and Knockando a path leads northwards over the hills to Birnie with its Class I symbol stone, pre-200 AD settlement and Roman fortlet, and then on to Elgin and Burghead. This path, today called the Mannoch Road, would come to link these two important church sites of Knockando and Birnie, although it’s not clear if any churches were established at either location in the Pictish era. Certainly there are no Christian crosses to suggest so, only pagan Class I stones. (For more detail on the church lands of Knockando, this is a great site.)

Another route goes from Knockando to the northwest eventually reaching Forres. Add to this, the routes up and down the Spey valley, and the route north to Knockando via the River Avon, all converging to make Knockando an ideal central gathering place. Logistically, Knockando may not just be a local assembly point, but an inter-regional gathering place for festivals.

Knockando

Knockando is pronounced with an emphasis on the middle element, so it is divided as Knock-Ando. The element knock/cnoc is a later introduction to Scotland and the -ando element has been proposed to be ceannachd ‘trade’, giving us ‘Hill of Trade’. But this explanation isn’t straightforward, this from William Patterson:

ceannachd shows a genitive ending -a, which presumably survived in Scottish Gaelic when the name Knockando was fossilised into Scots. Both instances of ch in cheannachda would presumably have been elided in regular use of the place-name. There does not seem to be an ideal explanation for this process, and some different explanation would not be out of the question.

Actually, cennach ‘transaction’ ‘bargain’ looks more promising for closer correlation to the place-name. Note the spelling variation with a -d-, cendach. North-east Scotland was conservative with pronunciation of both consonants in the -and present participle in Scots, which indicates that the same may have been true in its former Gaelic speech. The genitive of cendach is given with the expected form cendaig(h) and with cheandoigh. Especially given that -o and -ie endings can be interchangeable in Scots spellings and pronunciations, this comes close to the sound in Knockando. The hint at ritual connotations of cennach is of interest.

This name indicates that Knockando became a location for markets and trade at a later period. But it doesn’t necessarily imply a traditional assembly or ritual site in Pictish times or before.

DUBH dubaib rathib rogemrid ‘in the dark seasons of deep winter’

There is something odd to mention, three places with a spoked wheel icon feature this word dubh ‘black’. Is this mere coincidence of a word which is admittedly fairly common, or is something else going on here?

Even though it’s considered that Knockando means ‘Hill of Trade’ and does not contain -do (dubh ‘black dark’), there is a strange concentration of other placenames around there that do have the -do/dow/dhu ‘dark, black’ : Tomdhu/Tomdow and Cardhu, Cadha Dubh, Caochan Dubh, Strondow, Boldow, Kerkdow, Blackhillock, Blacksboat, Black Roads, Hill of Black Roads.

The Gaelic name of Tain is Baile Dubhthaich, and the general assumption is that this is the name of an 11th century saint Dubthach, a name which has dubh as its base. However, there is only one other place with a possible dedication to this saint, Belmaduthy on the Black Isle, which doesn’t offer much confidence in the existence of such a saint.

And in Ireland at the great Neolithic complex of Bru na Boinne, the mound Dubad ‘Dowth’ also has this same word at its base. Dowth famously has several spoked wheels on one of its kerb stones. And one of its passages orients to the setting winter solstice sun, an important connection I’ll return to later.

Assembly and sanctuary placenames

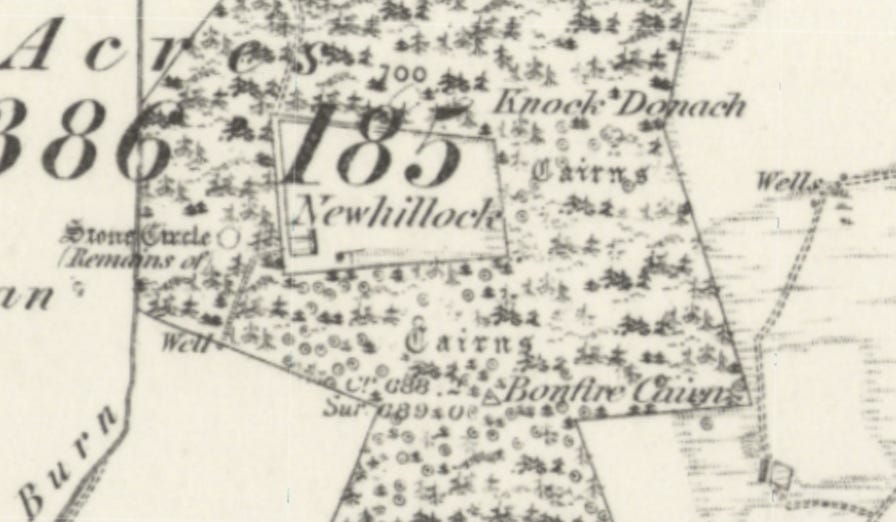

A kilometre above Knockando is a small hill called Newhillock (today called Knock Donach). Of course, hillock is English, but hills are not ‘new’. Ancient sacred places were often called a nemeton ‘sacred place’, and there are many still visible in Scottish placenames to this day. The word nemed can at times distil into ‘new-/neu-’, which raises the possibility that this name is a trace of the earlier presence of such a nemeton. Older forms of Newhillock are Knowehillock and Knowiehillock, but is this an attempt at Anglicisation of an older ‘new-? Much would depend on whether the initial K- was still pronounced in this area when these forms were used. If these Knowe- forms post-date the loss, something which can’t be said either way, the ‘Knowe-‘ could be attempts to make sense of an element ‘New-‘ (‘nemeton’) that would no longer make any obvious sense.

Also on this hill are Bonfire Cairn and Knock Donach ‘Sunday Hill’(?), plus a number of cairns, wells, a stone circle, and a chapel. Taken together, this group strengthens the possibility that we have here an ancient nemeton.

The one name that is least easy to dismiss as irrelevant is Bonfire Cairn. Precisely because its location does not seem spectacular, as the top of Ben Rinnes is for instance, there must have been some other reason for its location there, and the group of cairns long before. This does imply a view to somewhere else, rather than towards the site. Logically, this view is to Ben Rinnes.

A 1671 table of medieval lands includes two intriguing names which unfortunately have no location given: Tamair for Teamhair (?) (the same term for Tara the seat of the High-kings of Ireland), and Achinenie which may be Achadh an aonaigh(?) ‘Field of Assembly’. (An excellent site for other placenames in this location is here.)

Glencumrie

Finally, the name Glencumrie, now disused, is of particular interest, as this looks as if it may contain the word comraich ‘sanctuary’.

"… the lands of Knockandoch and Glencumrie, alias Knockandoch, pertaining to the chaplainry of St Andrew, founded within the cathedral kirk of Moray, with the pendicles and fishes thereof upon the water of Spey … [Fraser, Wm. (1883) The Chiefs of Grant, III, 456-458.]

The placename scholar W.J. Watson only mentions two uses of this term applied to a sanctuary, Applecross and Tain. If this analysis of the placename Glencumrie is correct, then here once again, we have two Pictish sanctuaries, Tain and Knockando, both with spoked wheel symbols, the same spoked wheel icon that is found as votive pieces in their thousands at sanctuaries all across the Celtic world.

The OIr. version commar shows that the meaning can be a confluence of people or troops, that is, an assembly or meeting-place, which does match very well the idea of a meeting place where routes converge. But it can also be physical, a confluence of rivers, or a confluence of hills (i gcomraibh cnoc). Comrie in Perthshire (Commar + suffix ach.) is presumed to be named for its river confluence (although I do wonder if it is both river confluence and meeting place, as assembly places could logically be located where paths along different river valleys converge).

The evidence so far

Well, so far we have a number of suggestive placenames that point to the area around Knockando likely being an ancient assembly place (Achinenie ‘Field of Assembly), a sanctuary (Glencumrie “Glen of Sanctuary/Assembly), a nemeton (NewHillock ‘Nemeton Hillock’), and a later trading place (Knockando ‘Hill of Trade’). And we have other intriguing names such as Donach Hill (Sunday Hill), Bonfire Cairn, and Tamair (Tara ‘Outlook Place’). Naturally, not all of these may be diagnosed correctly, but taken as a whole, its hard not to see Knockando as a key regional assembly site.

To the placenames, we can add in the convergence of a number of paths, and above all, the presence of the ancient spoked wheel symbol. The question though is why this place? Why is Knockando so special? And what was happening here?

In Part Three of this blog KNOCKANDO: A PLACE OF FESTIVAL, I will look at the symbols of the second Knockando stone to see if this symbol stone can support this picture of a sanctuary, and then I will explore how this place of assembly at Knockando might be functioning.

And just because it’s beautiful, another photo of Ben Rinnes: