SUENO’S STONE AND THE SMALL FIGURE ICON (PT 1)

Locating examples of the same icon on other stones and looking at their context

This story started as a question about an odd panel on the massive Pictish stone near Forres in Moray, called Sueno’s Stone. The panel shows a small central figure flanked by two much larger thin figures bent in a sort of oval around and over the small figure. The figure on the left holds an axe over his shoulder, a common type of axe seen on other Pictish stones. Two smaller figures are on the outer edge. The identification of the scene on this panel has long been a mystery.

This strange panel is at eye level and below a massive Pictish cross covered in intricate interlace. That this small figure icon is depicted along with the cross, and by its own without other iconography around it, presents a picture of something which must have been of key significance for the Picts. But, what?

Sueno’s stone is the biggest Pictish stone ever carved. Its reverse is covered by serried ranks of warriors, and scenes of beheaded corpses. While this small figure icon isn’t on the same side as the battle scenes, it still raises the question of whether it is also related somehow to a battle context?

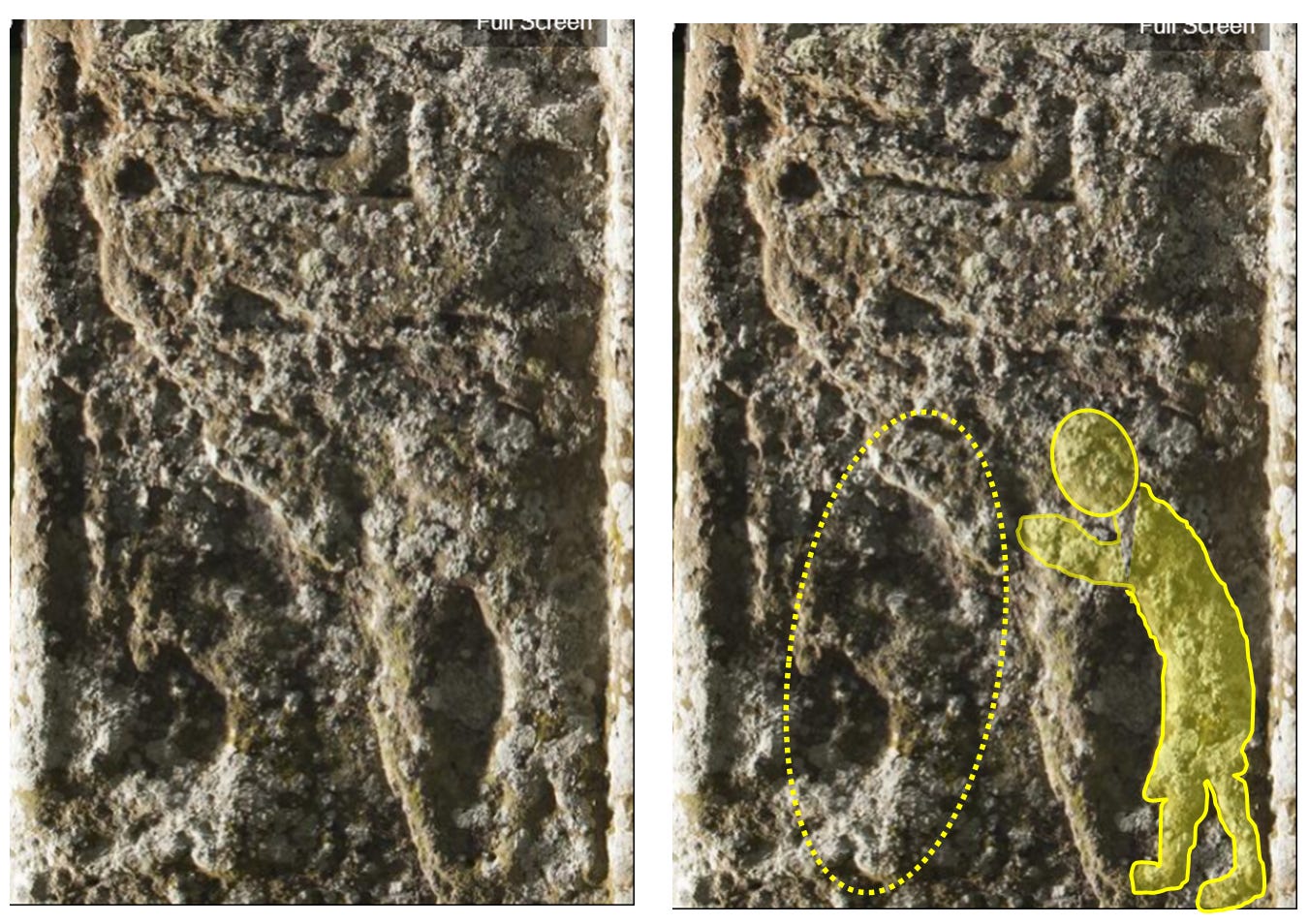

The panel itself is extremely worn and its details largely unclear. But, there are several other stones with a similar small figure icon, and we may be able to further understand this icon by looking at these other examples.

The other stones with a small figure icon

GASK A similar panel may be on the Gask stone, overlooking the Dunning monastery, and close to Forteviot, a centre of political power at least by the early 9th century. The lower LH side of the cross shaft has a leaning figure and another facing it, similar to the figures that form an oval surrounding the small figure on Sueno’s stone. Unfortunately, the surface of this stone is extremely eroded, so the details aren’t clear. But the leaning and encircling stance of the figure that can still be made out is otherwise unusual in Pictish art.

This stone has Pictish symbols on the reverse, although they are quite small and on the lower RH panel, as if in the process of losing their importance. It’s difficult to date a stone like this, but it is late in the closing CII period, in comparison to Sueno’s stone which has no symbols and has just crossed into the CIII period (while remembering these are artificial classes for ease of reference by modern scholars and in fact may not be completely sequential in dating). So it’s possible that both Gask and Sueno’s stone come from the same period, or one close to the same.

ST ANDREWS, FIFE There is another stone, much smaller this time, from Saint Andrews in Fife, again another key religious centre, established as a monastery by Oengus I in the mid-700s, and most of the Pictish stones here can probably be dated to activity in a few decades in the mid-700s. Here we have another small figure, flanked on the left by a man with a sword over his shoulder, while the figure on the right holds a Pictish round shield over the head of the small figure. The small figure is not being attacked by the figures with weapons. The position of the shield over his head appears to be protective.

Below this are two confronted beasts with a human head between their jaws and two birds above, the occurrence of which is unique in a Pictish art context, but if seen in an Anglo-Saxon or Norse context would no doubt lead to a discussion as to whether this is symbolic of Woden/Odin with his two ravens speaking into his ears and his two wolves, Geri and Freki, who roam the battle field "greedy for the corpses of those who have fallen in battle".

Odd though this solution may seem, we shouldn’t throw it out without further consideration, as there is a growing body of evidence for Anglo-Saxon, mainly Northumbrian, influence within Pictland during the 700s. St Andrews itself is considered to be founded by Oengus I with the assistance of Bishop Acca of Northumbria, so an Anglo-Saxon influenced piece of artwork isn’t out of the question. As well, the icon of the two ravens of Odin talking into his ears is so prevalent in both Germanic and Norse artwork and myth, that it would take special pleading to claim that someone created the same image but meant something entirely different by it.

In Celtic artwork, the raven is commonly used to signify that the person portrayed is dead, and in Celtic mythology ravens are also said to eat the battle dead. So it’s possible that both Germanic and Celtic lore are being melded here to indicate the same context – the battle dead.

The Alt Clut examples

The small figure icon is also found on another three stones, but this time in the Glasgow area, Barochan, Cambusnethan, and perhaps Govan itself.

It is definitely an expected turn of events to find an icon used both in Pictland and the Brittonic kingdom of Alt Clut, but it is even more unusual to not find even a hint of such a scene on any other cross in Britain or Ireland. All these crosses with their small figure icon can be linked through their uniqueness, linked in theme and concept, linked no doubt within a short period, but how might they be linked beyond that?

CAMBUSNETHAN The first is a fragment of a cross shaft from the church of St Michael at Cambusnethan, which has a small figure flanked by three larger figures, with their arms over the head of the small figure, although the details here are eroded away. The figure on the far left appears to hold a sword over his shoulder, similar to the St Andrews scene.

BAROCHAN The second cross near Glasgow is the major cross of Barochan, over the river Clyde to the south of the stronghold of the Britons at Dumbarton Rock. Here the small figure is once again flanked on the left by a man carrying a weapon, this time an axe as on Sueno’s stone, while the figure on the right holds some sort of item above the head of the small figure.

But it is what is on the panel above the small figure icon that gives pause, it is a single rider being greeted by a standing figure holding out a drinking horn. This quite common type of icon is neither Pictish nor Celtic, but Germanic and Norse, usually interpreted as Odin, or a warrior of Odin, being greeted by a Valkyrie female as he arrives at Valhalla, the great feasting hall of the warrior dead.

Below the small figure icon is a pair of confronted beasts with gaping mouths, similar to the St Andrews example but without the accompanying head and birds. (However, an earlier researcher, Mann, reported in 1919 that there was a head between the beasts’ mouths.) If this is the case, then once again we have Odin’s wolves under the small figure icon, just as on the St Andrews stone. But here the Barochan small figure icon is sandwiched between two Odin-related icons, Odin arriving in Valhalla above and Odin’s wolves below, and that strongly implies that the small figure icon too may well be related to Odin. And that throws the source of this small figure icon into question. Should we be looking for a Germanic/Norse source?

The other side of the Barochan stone has ranks of figures and a line of trumpeters, declaring its ‘prominent martial imagery’ according to Driscoll1. And it is this rare depiction of lines of battle figures that connects it to Sueno’s stone with its serried ranks of troops, something which is not seen elsewhere in Pictish art.

Neither the Barochan stone nor Sueno’s stone are located at a known church. Driscoll says this ‘may lend credence to the notion that its original context was primarily secular’. The primary candidate for this secular context could well be an actual battle of major importance.

GOVAN With two crosses in this region, Cambusnethan and Barochan, both with a small figure icon that stands out on these crosses as important, we might expect to also find one at Govan, with all its carvings at a key religious centre. And there may be, on the ‘upside down cross’. The entire icon is small and oddly situated on the side panel, but again it appears alone as if holding special significance in its own right. Unfortunately, it is too eroded to see the small figure clearly.

It’s not clear if this is meant to be the same small figure icon, as uniquely here the icon has a large seated figure to the left, rather than a standing figure with a weapon over his shoulder. The figure to the right once again holds an item above the head of the small figure, this time a small square. If the round item on the St Andrews stone is correctly identified as a round shield, then here on the Govan stone, this would be a small square shield. The Picts are portrayed with both small round and square shields on other stones.

But, the other faces of this cross have worn completely away, so there is no way to tell if this cross had other military aspects to it. For the moment, this may be a version of the same small figure icon, but then, may be not either.

The battle trumpeters

As well as the small figure icon, the Barochan stone has other unusual connections to Sueno’s stone.

On the other side of the Barochan cross is a line of trumpeters, blowing trumpets upwards, and above the trumpeters a row of men. Sueno’s stone also has a similar line of trumpeters in a scene of battle and beheading. The stuicc chatha ‘battle trumpets’ are mentioned in Irish texts, and an actual trumpet has been found in the River Erne, 58 cm long, made of yew with brass bands, and dated to 750 AD.

The Barochan stone was not located at a church, but on the main route leading north across the ford to Dumbarton Rock. Barochan Hill was the site of an Agricolan period Roman camp, which may have still been recognisable as such at the time the cross was carved. This has been identified as Coria of the Damnonii, a Celtic word for ‘hosting place’. Add to this its icon of a warrior arriving in Valhalla, and the wolves of Odin below, the lines of warriors, and then the trumpeters that we see involved in warfare on Sueno’s stone, all set out a strong military theme for the Barochan cross. So, the military contexts of both the Barochan stone and Sueno’s stone does support the idea that the small figure icon is also associated with battle. And that both stones were either hosting places or sites of actual battles.

DOGTON, FIFE Trumpeters are a rare sight on carved stones, and there are only two other stones apart from Barochan and Sueno’s. The first is a free-standing cross shaft, at Dogton in Fife. Unfortunately, the stone is very eroded so it hard to make out. But it too may have a rider with a figure before it as on the Barochan stone, and below that panel appears to be a couple of trumpeters similar to Barochan and Sueno’s. This time there is no small figure icon with these two panels (that we can now see due to its eroded state), but finding icons that go together on multiple stones does suggest that the Dogton stone is another ‘battle’ stone, possibly marking the site of an actual battle. Alternatively, the area, just inland from landing beaches in the Firth of Forth, may have been an ancient hosting place, a place to gather men in the face of invasion from the south.

ST ANDREWS (another one) There is yet another stone at St Andrews which may have a single trumpeter standing behind a half-size figure, a picture which is a little different to the other small figure icons but is possibly still part of this same theme.

The connections between stones with this small figure icon

Below are the stones with a small figure icon, grouped together for comparison.

All these icons focus on a small figure at its centre. In Pictish art the most important figure in a scene is usually slightly bigger, not smaller. There are two possible interpretations of this, that the central figure is a small child, or that the flanking figures are far more important, possibly deities.

The figure on the left holds a weapon, three times a sword (St Andrews, Govan, Cambusnethan) and twice an axe (Barochan and Sueno’s), with Gask now too eroded to tell.

The figure on the right either holds a shield on some item above the small figure’s head, or their body is bent around it as if to protect it.

On all stones this icon occurs with or on a cross, but most critically, it isn’t just one panel amongst many, it is usually alone, the implication being it holds a key significance.

Yet this icon isn’t a common theme on other crosses across Pictland, and it doesn’t occur outside these few locations.

The icon occurs in both Pictland and the kingdom of Alt Clut, but at places which may have an Anglo-Saxon connection or influence.

These stones have other features in common, such as warriors, trumpeters, and confronted beasts, which places this icon into a military context. On both the Barochan and St Andrews stone, accompanying icons appear to be of Woden, again indicating a military context.

All these stones come from the late CII into the early CIII period, which probably means they can be dated to the mid-700s into the early 800s.

Making sense of the Sueno icon

The small figure icon on Sueno’s stone is quite eroded, but given the pattern of the other instances, we can now try to redraw an interpretation. The flanking figure on the left is not holding the small figure’s arm, but holding the shaft of his weapon, a Pictish axe of form seen on Golspie and Aberlemno3. The righthand flanking figure is too eroded to be sure, but if the pattern holds, he will be holding a shield over the head of the small figure, not holding the arm of the small figure.

The next step

So far, I’ve collected the examples with a small figure icon, and found several related battle-focused stones with trumpeters and warriors. And I’ve noted the key facets of the icon - a central small figure with a larger figure holding a weapon over his shoulder to the left, and another larger figure to the left holding a shield in a protective stance above the head of the small figure. All of which has allowed me to try to redraw the Sueno’s stone icon, putting it into the context of the other examples.

In the next part of this blog, I will look at the potential significance of the small figure icon, the various theories, and try to find a solution that will fit the battle context of these stones.

Driscoll, S.T., O'Grady, O. and Forsyth, K., 2017. The Govan School revisited: searching for meaning in the early medieval sculpture of Strathclyde. In Able Minds and Practiced Hands (pp. 135-158). Routledge.