SYNTAX OF THE PICTISH SYMBOLS (PART 1): FACE

Analysing the rules that determine the direction a symbol faces

This is the first article I intend to write in a series about the syntax of the Pictish symbols. The symbols aren’t just put willy-nilly on a symbol stone, they must obey certain rules, their syntax.

I will be dividing this analysis into sections looking at different aspects of the syntax, but admittedly they all work together on a stone, so it’s often difficult to discuss one aspect without involving another. The aspects I will discuss in this series are:

Face (this blog) – the direction a symbol faces

Order – the structure of the ordered list of the symbol set

The Mirror – reverses the order on a stone

The Mirror+comb – reverses the dominance on a stone

Losing a rod – the symbol loses dominance

The process

The first step in this analysis has been a long one, creating a full dataset with information about each symbol, and whether it definitely did or didn’t have an accompanying mirror+/-comb, or whether its mirror+/-comb status was no longer known due to erosion or fragmentation. The analysis and establishment of the syntax rules took even longer, a process over many years, a circular process of finding what symbols fitted into what rules, then retracing the steps to investigate the exceptions, redefining the rules, re-analysing the results, time and again.

The foundation of this work was originally done around the year 2000, and presented at the Fifth Australian Conference of Celtic Studies held at the University of Sydney in July 2004. My special thanks are to the late Dr Bob Henery for his support and meticulous review of the initial drafts. Summaries of this work were published in the Pictish Arts Society newsletters, starting in number 98 of winter 2020.

Symbols come in pairs

Pictish symbols usually come in a pair – why no one is yet sure. It is the single most mysterious part of the puzzle, and will be critical to solving their meaning.

Sometimes there are 4 symbols (2 pairs) or an even longer series of pairs on later Christian stones. We occasionally find a single symbol on its own, but this happens when other sorts of oddities are also happening as the symbol tradition moves into its final stages, after perhaps 800 or so years of standard symbol usage.

The symbols show a truly astonishing consistency of usage, through seven or eight centuries, and all over Pictland. This rigid standardisation gives us confidence that there is structure and logic behind the symbol stones, just waiting to be discovered.

(All photos in this blog are taken from STAMS and CANMORE).

Identifying the face of a symbol

One of the most obvious differences in the way symbols present is the direction in which they are facing, what I am calling here their ‘face’. Symbols have two faces, they face either to the right (RH) or to the left (LH).

By direction, I mean the direction the symbol faces as we look at it. Beware that some writers use the direction that the stone contains, as if you need to imagine being the stone itself, which I find unnecessarily confusing.

For most animal symbols it is relatively easy to identify if the animal is facing to the right or left. For abstract symbols, their face isn’t quite as obvious, but the orientation of their righthand (RH) and lefthand (LH) faces can be assigned by matching them to an animal symbol in a symbol stone pair, and then by progressively cross-matching them to other RH or LH versions of each type of symbol as they become identified. In this way, we can build up a list of what is considered RH or LH versions of each symbol.

Many symbols have attested RH and LH forms. The less frequent ones only have one face attested, although its relatively safe to assume these are RH forms as this is the most common face by far. However, it’s probably safe to assume all symbols do have a LH and RH face, whether we have examples or not.

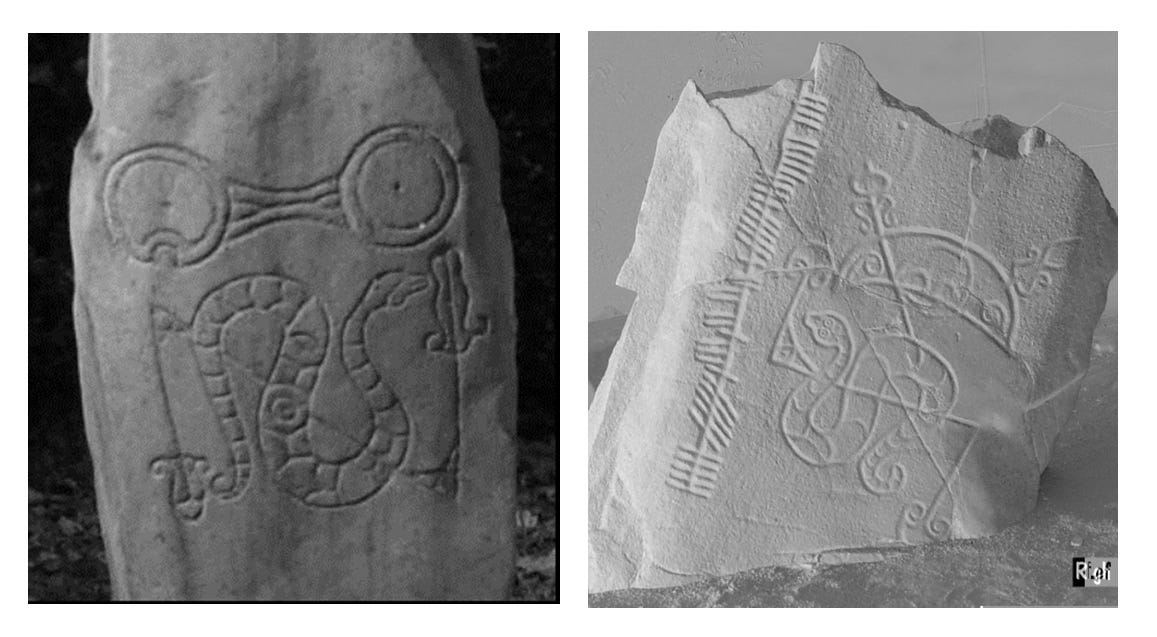

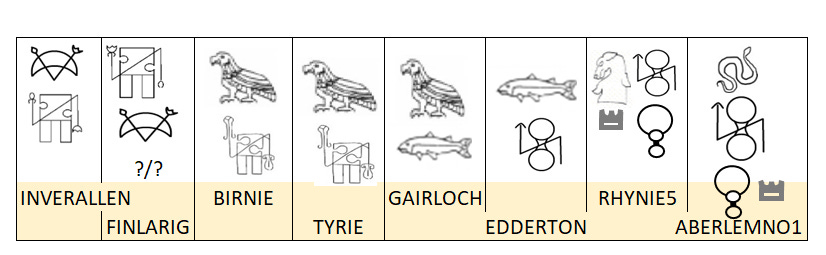

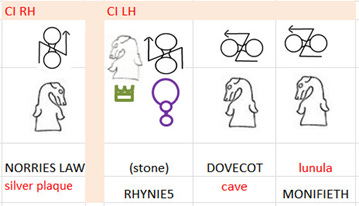

The following are examples of symbols identified to their RH and LH forms.

Some abstract symbols, like the animals, merely mirror their forms left to right. But, rotating some of these abstract symbols on the horizontal plane through 180 degrees has no effect, for example, the cauldron symbol with its handles in the horizontal plane will appear the same when rotated. In this case, the left-hand version of the symbol is created by turning the symbol through 90 degrees only, so that the symbol appears to be in the vertical plane - in the case of the cauldron symbol this will put the handles near the top and bottom instead of to each side.

In the case of the rodded symbols, their left-hand counterpart can be formed by mirroring the rod right to left, so that the rod ends are reversed. A RH symbol always has a rod pointing to the top RH corner, a LH version points to the upper LH corner. Sometimes, the body of the symbol is also turned 90 or 180 degrees, but the face seems to be dictated primarily by the direction of the rod.

The case of the double-disc/Z symbol

The double-disc/Z symbol is more complicated as it has two possible RH and two possible LH versions. On CI symbol stones we have 23 double-disc/Z symbols with the discs horizontal and the Z rod pointing to the upper right – the RH form of the symbol. This same RH form with horizontal discs continues as the main form into the CII group with 20 instances.

Rhynie2 is unique – a RH symbol but with vertical discs. This stone in size and state of erosion and position appears to be a companion of the Rhynie Spearman, and is therefore possibly one of the earliest symbol stones. Its unique setup may be indicative of the faces of symbols not yet being standarised at time of its carving. But, although unique on a symbol stone, this form is also found on a silver chain and a plaque – which suggests that on mobile objects we don’t just have LH forms, but mirrored forms of the RH form.

The seven CI LH instances have discs arranged vertically, with their rod pointing to the top LH corner. But for CII stones, there are only two LH vertical examples. Instead, we find a new form appearing, with horizontal discs instead of vertical. This is the only case on the symbol stones that I am so far aware of where it looks like the standard accepted form of a symbol is shifting over time.

It appears that it is the direction of the Z rod which gives the symbol its face, not the arrangement of the two discs. If a Z rod is pointing to the upper right, it is right-hand, and if to the upper left it is left-hand.

Another important thing to note here is that only the LH form of the double-disc/Z is used on mobile objects and cave walls. This is a typical situation which we will return to in a minute.

Why is a RH or LH face chosen for a particular symbol?

Of the CI symbols that can be defined as either RH or LH, the overriding preference is for RH symbols, with a right to left ratio of 6.7 : 1.

This preference however changes dramatically for CII stones, with a ratio of only 1.26 :1, which is not far from random. To some degree, this is driven by the symbol pair gradually being moved from a high position of importance, to being placed in a subordinate position on the righthand side of the cross, but facing the cross stem, making the symbols themselves lefthand.

There are only two symbols which have more LH instances than RH, the snake/Z with 2 RH and 14 LH, and the divided-rectangle/Z with 3 RH and 9 LH.

Many of the less frequent abstract symbols do not have a second face attested, but there seems no reason to presume these forms do not exist. Given the relatively high frequency of right-hand symbols, it is likely that most, if not all, of these attested infrequent symbols are the right-hand form.

The fact that the symbols are predominantly right-hand indicates that the symbols are functioning within the cultural context which we would expect of the Picts as a Celtic language speaking group. In all Celtic languages there is an integral sense of sun-wise direction, to the right is the correct and good direction to move in accord with nature. The Irish word deas (Old Irish dess dil.ie/15783) means ‘right’, ‘good’ and ‘south’, ‘south’ being the direction of the sun, and ‘right’ the direction in which it moves. From this comes the word deiseil (Old Irish dessel dil.ie/15791), ‘southward’ or ‘sun-wise, the direction in which it is proper to circumambulate a sacred object such as a well or a church.

On the other hand, the word tuath, ‘left’ and ‘north’ dil.ie/42241, has the opposite negative connotations. Which raises the question why a lefthand symbol would ever be chosen.

Why chose a RH or LH symbol?

Some external factor appears to be dictating the choice of face for each symbol on a stone. The hope is that once more is understood about the rules governing the symbol stones, it will enable further investigation into the factors driving these choices.

(I am currently working on an idea that the LH symbols have their referent to the north, and the RH symbols in the south. I’ll write more on this once I’ve presented the full picture of the syntax rules.)

Combining the same face in the symbol pair

The process of identifying symbol faces was only possible because most symbol pairs present with both symbols facing the same direction.

The majority of symbol pairs have both symbols RH, around 170-180 of the 202 pairs available (the faces of some symbol pairs aren’t yet identifiable).

There is a handful of stones, eight in total, where both symbols are LH. Configurations of both RH or both LH symbol pairs do not necessarily require a mirror+/-comb, although they occasionally may. (On the lists of symbol stones, if the presence of a mirror or comb is not evident due to erosion or fragmentation I’ve put a question mark under it.)

Combining a RH over LH symbol

There is another small group of nine symbol pairs (5%) that have a RH symbol over a LH symbol.

It is immediately striking that this group of symbol stones has a high frequency of mirror+/-comb. Only three of the 10 symbol pairs in this RH/LH set have an uncertain mirror/comb status having been trimmed down, Ballintomb, Brandsbutt and Drumbuie. The Picardy stone has only a sole mirror. None of this set definitely occur without a mirror+/-comb.

Jumping ahead here for the moment, we will see that for each symbol pair there is a dominant symbol, usually the upper one (I will discuss ‘dominance’ in a later blog in this syntax series). The role of the mirror+comb is to move ‘dominance’ to the lower symbol. In all these cases of the RH+LH symbol pairs with a mirror+comb (barring three where the stone is too eroded to tell), the dominance is given to the lower symbol which is the lefthand symbol.

The Picardy stone with its sole mirror reverses the natural order of the symbols but leaves dominance with the upper symbol. (Again, I will be writing about the order of symbols and the role of the mirror in another blog, but all these aspects of the symbol pairs work together so it’s difficult to write about one without involving the other.)

In summary, when a stone has a RH symbol over a LH one, it seems to somehow be connected to a stone’s need to transfer ‘dominance’ to the lower LH symbol, as evidenced by the mirror+comb. This process prevents the LH symbol being the top symbol - something which the syntax rules frown upon. However, the Picardy stone shows another way to combine a RH and LH symbol leaving dominance on the RH symbol.

Combining a LH over RH symbol

In comparison, there are only 4 stones out of the current total of 202 with a LH face over a RH face. Each of these stones has a question mark over it.

Advie is the only stone which clearly has a LH symbol over a RH one. It is unclear if Advie doesn’t have a mirror/comb on the eroded part of the stone. Advie is one of a group of LH crescent/V symbols that occur along the inner River Spey, although there is one LH crescent/V in the cave at Covesea, Moray.

Kintore2 is a stone that is weird and exceptional in more than one way - it holds one of only two CI LH Pictish beasts, but the reverse has a RH beast and the only mirror placed above a symbol, both upside down. Certainly, this stone breaks all the rules and is hard to explain, so the suspicion is that it is a practice stone.

Rhynie6 has a LH double-disc/Z over a RH crescent/V with a mirror underneath. To jump ahead for a moment, the single mirror normally signifies that the symbols in the pair are in a reverse order to normal, meaning that in a sense the RH symbol is noted as above the LH through application of the mirror. This Rhynie6 setup of a mixed face pair with single mirror does not occur elsewhere in the entire body of CI symbol pairs, so the question is whether on this one stone we have a rare but valid configuration. Alternatively, the designer may have simply got it wrong. It happens.

Drumbuie has a snake/Z (LH) over a double-disc without rod (RH). This odd configuration may have something to do with the double-disc losing its rod. It does however suggest that the rules don’t completely forbid a LH/RH setup, but that this setup is just not preferred.

Overall, it seems pretty clear then that the rules of syntax do not promote a LH symbol over a RH symbol. The preferred setup is a RH symbol over a LH one, but in four rare cases we do find a LH upper symbol.

In summary, the symbol pairs are 90% both RH, about 5% both LH, and 5% RH over LH, with only four cases of LH over RH.

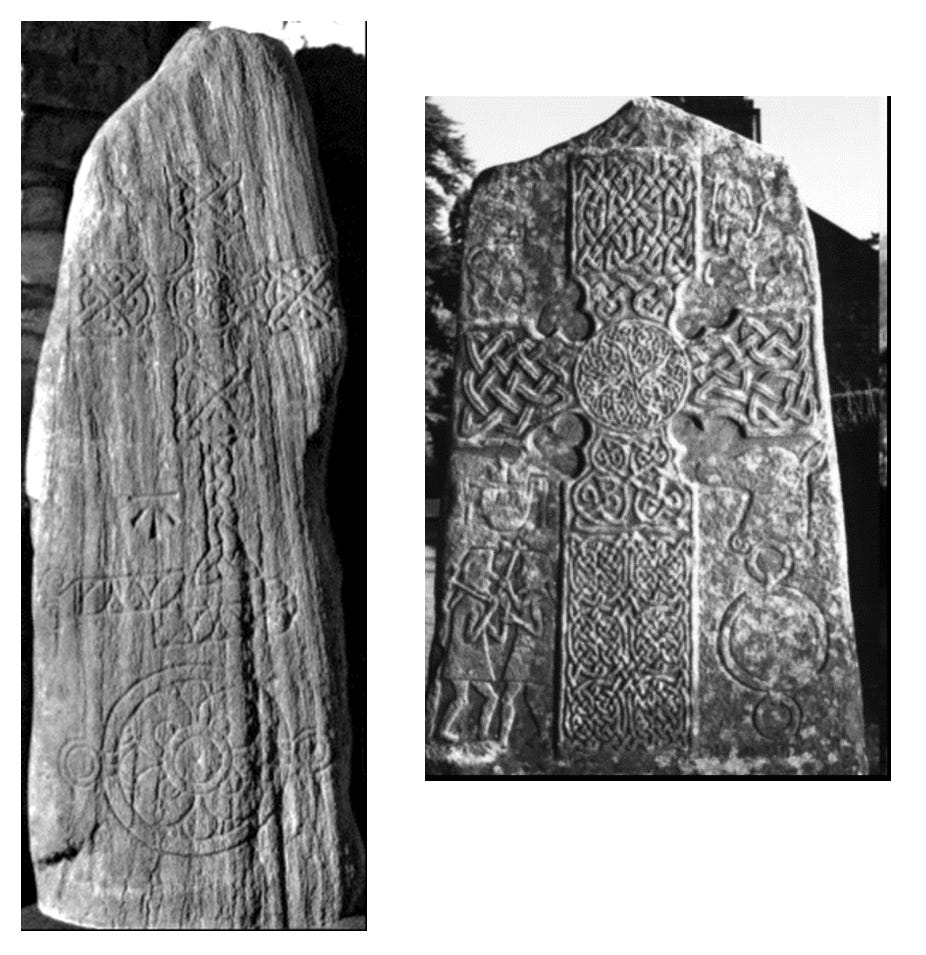

Changing face in the Class II period

But, here is a problem. Once we head into the Class II period, the symbol rules break down. Not on all Class II stones, the earlier ones seem to retain good symbol form and rules, but degradation soon sets in. In the case of the face of the symbols, we do suddenly have some examples where a LH symbol is above a RH symbol. The question is why? What is happening in this late period? Has the expertise behind the symbols been lost, and if so, how did that happen? Did people no longer care about the significance of the rules? Or were the experts themselves no longer around to advise and assert them?

Symbols in caves and on mobile objects

Symbols, and symbol pairs, also occur on the clasps of the Parkhill and Whitecleugh silver chains, on a mini lunula1, on a silver plaque from the Norries Law hoard, and carved on the walls of caves in Fife and Moray. There seems to be a general rule at play that symbols that occur on portable objects and places other than symbol stones tend to use the LH forms - the opposite trend to the preferred use of RH forms on stones - although some RH faces do occur.

The mirror+/-comb never occur on portable objects or cave walls, only on symbol stones, a clear indication that the mirror+/-comb is specific to the function of a symbol stone and how the symbol pair is organised.

The case of the double-disc/Z has already been laid out above, now let’s look at some other examples. The ogee symbol has a RH form which occurs on stones, but occurs as two LH instances on a silver chain and on a cave wall. This is a good example of the non-stone symbols preferring the LH face.

The notched-rectangle without a Z rod is a rare symbol, only occurring once on a stone fragment in Fife. But again, we find the LH form on a silver chain. We can tell which is the RH or LH form by comparison of the inlets to the same symbol with the Z rod.

The symbol of the otter-head appears together with a double-disc/Z on a miniature lunula, a silver plaque, and a cave wall. The otter-head occurs only once on a stone at a centre of Pictish power at Rhynie, where it is LH. The silver plaque from the hoard of Norrie’s Law in Fife, is the only RH pair. There is no other instance of a repeated symbol pair like this occurring across different media, and points to a highly significant meaning for the Picts.

Implications for symbol dating and evolution

On the wall in the Covesea cave, Moray, the salmon symbol’s LH form is rotated 90 degrees into the vertical, and is accompanied by a rare example of a LH crescent/V where the V rod ends are switched left to right. This is extremely interesting, as the crescent/V, despite being the most frequent of all symbols at nearly 20%, almost never occurs in its LH form. The only other few instances of the LH crescent/V occur in a series of symbol stones in the inner Spey valley, many miles from Covesea. In other words, the person who carved the Covesea symbol pair, possibly in the 3rd or 4th century, wasn’t just randomly copying a handy symbol stone that they had seen nearby, but rather they knew the syntax rules governing symbol pairing, the symbol order and faces and how to apply them.

This Covesea symbol pair with its two LH symbols in the correct order demonstrates that not only did the symbol set appear fully formed before we see them appear carved in caves and on stones, but the rules of syntax were also being applied from the very start.

In other words, we need to allow considerable time before the carving of symbol stones for both the development of the symbols themselves, and the rules that govern them. This is an extension of the observation first made by Dr Katherine Forsyth2.

the face of a symbol – what we know so far

Many symbols have a RH and LH face which can be identified.

The likelihood is that all symbols have a RH and LH face, although a second face is not yet attested for number of the less frequent symbols.

The RH face is strongly preferred, at least on CI stones.

Symbols in a pair prefer to be both RH (90%), or less commonly, both LH (5%).

If a mix of RH and LH symbols is required on a stone, then the LH symbol is placed in the lower position, and if needed may be given dominance on that stone by the addition of a mirror+comb.

A configuration of LH over RH symbol pair is at least strongly discouraged if not forbidden.

Symbols on cave walls or metal items strongly prefer the LH face, although they occasionally use a RH face.

The symbol rules break down on some later CII stones, with more LH symbols, and LH over RH setups.

The rules of syntax were present from the start of symbol stone carving, pushing the symbols and their rules back in time.

The reason which drives the choice of RH or LH symbol isn’t clear at this stage, but the rules make it abundantly clear that this choice of face is not random nor artistic, but caused by some external factor that is specific to the context of each symbol stone.

The next article on the syntax of the symbols will be about the natural order of the symbols and how this can be used to re-engineer an original ordered list.

Roger, J.C. (1880). "Notice of a drawing of a bronze crescent=shaped plate which was dug up at Laws, Parish of Monifieth, in 1796" . Proceedings of the Society of Antiquaries of Scotland. 14: 268–278.

Forsyth, K., 1995. Some thoughts on Pictish symbols as a formal writing system.