THE SYNTAX OF THE DOUBLE-DISC WITHOUT A ROD

In which I look further into the case of the changing order for the double-disc symbol, with and without its Z rod.

When I started this series of blogs about the syntax of the Pictish symbols, I had thought the symbols without a rod would be a trivial postscript to the story. In fact, it’s turned out to be the hardest, and most informative, aspect of all.

So in this blog I will begin an investigation into the use of a symbol which has lost its rod, in particular here, the double-disc/Z. But again, it was necessary to first go back and look more closely at the distribution and aspects of the double-disc/Z, the symbol that sits right on the bottom of the ordered list. And that led to the discovery that in the later CII period, the double-disc/Z suddenly started being used in the reversed order, as a symbol above others instead of always below. But what is the meaning of this sudden change in order for this particular symbol? What could be driving such a shift? This is such a dramatic change in the final stages of symbol usage, after many many centuries of strict symbol syntax.

For ease of reference, I have divided the Class II period into the earlyCII period, when a symbol pair is in the correct order, and the lateCII period when the double-disc/Z has a reversed order. There are a number of factors that also tend to occur on the lateCII stones, including a different type of cross, ogham and insular inscriptions, single symbols, and the use of the mirror+comb without any main symbol pair.

The double-disc without a Z rod

On Class I (CI) stones, there are few examples of the double-disc without a rod (FIG 1). And this is also the case for the other CI symbols that lose their rod – the snake, notched-rectangle, and crescent. Assuming the double-disc symbol is a variant of the double-disc/Z symbol and sits at the bottom of the list, then we have only three CI instances in the normal order according to the ordered list, and three in the reverse order.

Of those stones in the reverse order, the Inchyra stone also has ogham on it, and the Newton House stone has an accompanying stone again with ogham on it, indicative that these two stones at least are CI style of stones carved in the same lateCII period as the other stones with a reversed order. The implication is that all three CI stones with a reversed order come from the same lateCII period when the double-disc/Z is being allowed to be the upper symbol.

Rods can be used to indicate a symbol’s dominant or subordinate status in a symbol pair, with the subordinate symbol changing its rod ends to acknowledge the symbol with dominance ore precedence. It is reasonable to assume then that a symbol without its rod has lost its dominance, or to put it another way, has given up dominance in favour of its accompanying symbol.

The Class II double-disc without a rod

But the situation becomes far more extreme on CII stones (FIG 3). Here we suddenly have a fairly large group of ten CII stones with a double-disc without a rod, and all of them have the double-disc as the upper symbol, a clear violation of the syntax rules, but fitting with the same change in order as we saw with the lateCII double-disc/Z.

Again, this use of the reversed order with the double-disc without a rod as an upper symbol, when it should naturally be the bottom symbol, is consistent with a deliberate choice to use the double-disc/Z as an upper symbol in this lateCII period. These are not random mistakes.

In comparison, the notched-rectangle without a Z rod occurs only once on a CI stone, and never on a CII stone. The snake only occurs without its Z rod twice on a CII stone, while the crescent without its V rod only occurs 4 times on CII stones although two of those four (Meigle6 and Golspie) also have a double-disc without its rod. This rarity of rodless symbols shows just how exceptional this relatively large group of rodless double-disc symbols is in comparison.

The distribution pattern of these CII rodless double-disc symbols is similar to that of the double-disc/Z with a focus in the southern Angus region (FIG 4).

To summarise, the lateCII double-disc without its rod is acting consistently with the reversal in order, and the distribution focus shifting to Angus, already seen with the lateCII double-disc/Z.

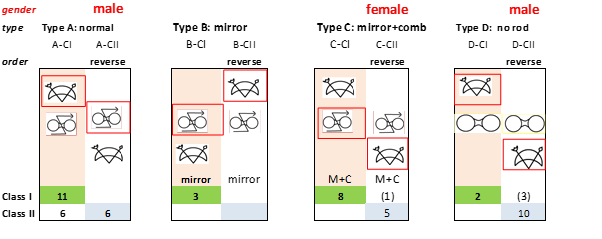

We can now pull all the double-disc+-Z data together and lay out the four normal configurations for the double-disc+-Z as seen for Class I and earlyCII stones (in orange), and their reversed lateCII configurations. The symbol with precedence is in the red box. (Here I am using the crescent/V as an example of the accompanying symbol, but this could be any other symbol.)

Defining CI stones carved in the CII period

From FIG 5, the figures in brackets are those Class I stones (with just two symbols) which are carved within the lateCII period when the syntax rules have changed: Keith Hall (Type C-CII) and Fyvie2, Inchyra, and Newton House (Type D-CII).

When I was looking at the order of symbols on stones, there was the problem that while most stones followed the correct pattern according to the ordered list, frustratingly just a couple of stones didn’t. One of those non-conforming stones was Keith Hall, a CI stone with an incorrect order. This stone might now be explained as a Class I stone which was carved in the lateCII period, when the double-disc/Z is allowed to be in the reverse order.

Although Class II stones must begin at a later time than Class I stones begin, it’s been impossible until now to ascertain for how long Class I stones continued to be raised during the same period as other CII stones. We now have some good indications of a CI-type of stone is being carved within the CII period – first, by having a double-sided comb, second, by having a reversed order double-disc+-Z, and third, by having an ogham inscription (although these may be a later addition to an earlier stone).

This means that some CI stones do continue to be carved right through the earlyCII and lateCII period. I have considered renaming these divisions more accurately as earlyCI-CII and lateCI-CII, but it is perhaps easiest to just use earlyCII and lateCII periods, remembering that this definition refers solely to time, and no longer refers to just stones with or without a cross.

How do we make sense of this dramatic change in syntax for the double-disc+-Z in the lateCII period?

Why is this one symbol suddenly allowed to take the upper position on a symbol stone? Why has there been this radical departure from the normal syntax on a symbol stone, a traditional that has held strong for many centuries up to this point?

This reversal in order for the double-disc symbol is not seen in other symbols, it is just this symbol that has a special need to reverse its natural order, so it must have a very strong and particular motivation for doing so.

A symbol of political power?

There is a possibility that the double-disc+-Z symbol in this late CII period has taken on a regional identity, the symbol of the Angus region, the heart of late Pictish power. Remembering here that previously CI double-disc/Z symbols strongly featured in the Aberdeenshire region, while only 3 examples of a CI double-disc/Z were found in the south, all with a mirror+comb. Could it then be the case that in the lateCII period when most examples are now found in the south, and the symbol is shifted to an upper position, that this change is a statement that all other regions now owe their allegiance to that southern power centre in Angus as represented by the double-disc/Z symbol?

A changing ordered list?

The ordered list of symbols has the double-disc/Z at its base, the very last symbol. But, if the symbols represent a list of items that is actually circular, for example think of a list of the constellations which actually lie in a great circle in the sky, or the months of the year, then it is possible to conceive of something occurring to shift the start and end of the circular list, resulting in the double-disc/Z shifting to the top of the list rather than the bottom. The Picts of this late CII period were living in an age where the constellations of the Bronze and Iron Age had precessed a full constellation, so this is one example where a shift in the list might be considered necessary to reflect a new reality.

That’s not to say that this shift is reflecting the precessed position of constellations, just to say that this kind of circular shift is one possible candidate, particularly when we are dealing with the very last symbol on the list. (The idea of shifting circularity comes from Erica Birrell.)

A changing attitude to gender?

There is another explanation to explore, and this one is about gender. In this late CII period, the mirror+comb occurs several times with a female icon, and it then follows that the same female gender is probably at play on the other stones with a mirror+comb from this same late CII period that have no icons to explicitly guide us as to gender. Notably none of these stones with a mirror+comb feature a male as the main icon. It stands to reason that if the mirror+comb is associated with women at this late period then the same concept is applied to all stones in this period, because it causes a distinct dichotomy in terms of gender which likely comes with implications for a division in personal status and function.

This Class II situation of associating the female gender with a mirror+comb may or may not be relevant further back on CI stones.

At the same time as we find the mirror+comb associated with a female, the double-disc/Z occurs several times along with a male icon, often a male horseman (e.g. Fordoun, Kirriemuir2 and Hilton of Cadboll). This suggests that the double-disc/Z may now be a strongly male-associated symbol.

When the double-disc/Z wants to take precedence on a stone, previously the only way to do this was by adding the female-associated mirror+comb which moves precedence to the lower symbol (normally the double-disc/Z, now male associated) in the pair. The new Class II configuration removes that clash of genders. By reversing the accepted order of symbols and allowing the double-disc/Z to act as an upper symbol, it allows precedence to be given to the male-associated double-disc/Z without calling on the female-associated mirror+comb (FIG 6).

There are two possible interpretations of this change in order and its potential linkage to the mirror+comb. The first is to say the role of the mirror+comb has changed and consequently forced a reversal in order for the double-disc/Z. The second is to point the finger at a change in function for the double-disc itself.

First interpretation: Has the function of the mirror+comb changed in the lateCII period?

The first interpretation might be that originally the mirror+comb did not equate to a female gender in form or function, but when this became the case on late CII stones, the use of the mirror+comb exclusively for women has introduced an internal conflict for the double-disc/Z when used for a man. However, this idea doesn’t explain why this reversal in order is only seen with the double-disc/Z symbol. If the mirror+comb had shifted its meaning, then we might expect a lot more lateCII stones to also show signs of changing their syntax to adapt to the new situation.

Although as a group LH instances are far fewer than RH instances, FIG 6 also demonstrates that most of the LH examples (7 of 9 LH compared to 7 of 36 RH) on both CI and CII stones occur with a mirror+comb. It seems likely that this grouping of the LH symbol with the mirror+comb means that both are somehow related to the female gender. Alternatively, there may be something else, a third factor, acting to draw these two factors together often, although on balance that seems a reach.

At the least, this similar pattern of the LH instance mainly used with a mirror+comb all through the CI and CII periods speaks to some consistency in usage through time. This does suggest that the mirror+comb has always been referencing a female association for a symbol stone. And this in turn indicates that the source of the conflict does not lie with the mirror+comb, but must be found elsewhere.

Second interpretation: Has the function or role of the double-disc+-Z changed in the lateCII period?

In my blog about the face of symbols and its possible connection to gender, I had trouble with the double-disc/Z as a predominantly RH facing symbol which should then be female if the general picture holds. This does make sense of the Class I symbols, where the double-disc/Z gets precedence when with a mirror+comb, with the proviso the mirror+comb itself has a female association in the CI era. If this is so, the implication is that it is the double-disc/Z symbol itself which may have somehow, strangely enough, changed its gender, to now be associated with the male. Alternatively, perhaps the double-disc/Z originally could be associated with either a male or a female role or function, but in this later period it strongly prefers to be associated with a male role. The temptation here is to suggest that this would fit the introduction of Christianity and the subsequent rise in dominance of men holding the most powerful roles, directly impacting the function of the double-disc+-Z. (from Linda Sutherland).

Gender and removing the rod

The sudden occurrence of a large group of double-disc symbols without a rod, likely betrays a motivation behind the reversal in order. Sometimes it is the exception that gives us the best information.

I’ve already spoken about the use of the RH version of the double-disc/Z in this lateCII period often occurring with a male icon, indicating it is now largely, if not solely, referencing a male role. Looking now at this group of double-disc without a rod, we have 7 out of the 10 examples having male icons on the same stone, mostly male horsemen, but on Golspie and Shadwick we have two standing male figures. I have marked these stones with male icons in dark blue in FIG 7. This strong grouping implies that the double-disc too is now referencing a male association.

The double-disc without a rod gives precedence to its accompanying symbol, assuming that the loss of a rod signifies the loss of precedence. But this makes the configuration of a rodless double-disc over another symbol (Type D-CII) effectively the same as the double-disc/Z over another symbol with mirror+comb (Type C-CII). So why don’t they just use the mirror+comb configuration of Type C-CII? The answer might be - because a particular stone wants to mark this symbol configuration as male-associated (Type D-CII) but without marking it as referring to the female gender with a mirror+comb (Type C-CII).

The story at this point seems to be heading in the direction of a change in usage for the double-disc+-Z in the lateCII period, that a symbol for a role that could earlier have been held by either a man or women, was now is only held by a man, a situation that brought it into conflict with the female-associated mirror+comb, a situation which was then rectified by a reversal in order.

The interaction of the two symbols in a pair

One of the major elements of this Pictish puzzle, is that there are two symbols in a symbol pair, and while I am doing my best to neutralise the effect of the second symbol with a double-disc+-Z, the stone itself must take into account both symbols at the same time.

At this point in research, I can’t yet firmly identify the gender associated with all the other symbols, and how that plays out in a symbol’s form, LH or RH, with or without its rod. So the next diagram (FIG 9) is a best attempt for the moment. Uptil now I’ve just used the crescent/V to stand in for the accompanying symbol in my diagrams, but here I note the gender of the actual symbol accompanying the double-disc/Z.

But, here’s the result (FIG 10) when I try to do the same exercise with CI period symbol pairs – there is simply no difference to see in how the proposed genders for the symbols are working in each configuration type. In other words, the role or function of a symbol has changed from something that both men and women could perform in the earlier CI period, to one that has a more clearly differentiated gender role in the lateCII period.

Whether this change in gender applies to other symbols, or just the double-disc+-Z, remains to be seen. The double-disc+-Z uniquely is able to change its order simply by virtue of being the final symbol at the bottom of the ordered list, other symbols do not have this option.

Thoughts so far

In the late CII period, the double-disc+-Z reverses its order in symbol pairs, from being the symbol naturally at the base of the ordered list and so the bottom symbol in a pair, to a symbol which occurs as the upper symbol of a pair.

It is only this one symbol, the double-disc+-Z, that acts to change its natural order.

The double-disc/Z is found with an accompanying male icon on some late CII stones, implying it is now a strongly male-associated symbol.

Changing the order of the double-disc/Z gives precedence to the male double-disc/Z symbol as the upper symbol of a pair. And it allows this symbol to be used in configurations that do not involve the female mirror+comb.

The lateCII symbols may be being used to represent roles in society, and what we are witnessing here is a shifting of those roles to men, under the growing influence of Christianity, and changing patterns of civil authority. Or rather, a shift in differentiating the roles which can be held by men or women.

The shift in the role and gender of the double-disc/Z may also be linked to a change in politics and power, with the southern regional group in power in the Angus region in this lateCII period using the double-disc/Z as their most frequent symbol, and identifying with it as their primary symbol.

The role of the double-disc/Z is seen as crucial, so critical to the Picts of the lateCII period, that this particular symbol is allowed to break all the centuries of rules about symbol order.

It may even be that these factors are connected. If the role represented by the double-disc symbol is a very powerful one, let’s say the role of kingship itself, then it might be that the stones of Angus have a concentration of this symbol because the symbol’s status of kingship is relevant to this regional centre of Pictish kingship. And this same powerful status is the force driving the symbol’s role now needing to be differentiated as to whether it refers to a male or female ruler, and so causing a necessary shift in its normal symbol order to accommodate that new gendered requirement. Effectively, this would mean that this is the period when rulership of Pictland is changing, becoming a male-dominated role.

Whatever the precise answer is here, what we are witnessing is a paradigm shift in the Pictish worldview in this late CII period, a period which encompasses the 700s AD.