KNOCKANDO: A PLACE OF FESTIVAL? (3)

in which I look at the second symbol stone and what it may tell us about a possible gathering place

In my first two blogs Knockando, KNOCKANDO, MEIGLE, TAIN, AND THE SPOKED WHEEL (1) and KNOCKANDO: LOOKING FOR A LOST SANCTUARY (2), I looked at the ancient spoked wheel symbol and place names found at Knockando, and what this might tell us about the location – a possible sanctuary, a possible nemeton, a festival assembly, and a more recent market place. Now, I will look at the other symbol stone, Knockando2, and what evidence we can gather of the function of such a gathering place.

Knockando2 also carries a very important ritual-associated symbol on it, the so-dubbed ‘flower’ for lack of better, which of course is no such thing, but it’s such an odd shape that no-one could come up with anything better! My current thinking is that this symbol represents ‘fire’, or something closely associated with fire. I could be wrong, but I’ll be calling it the ‘fire’ symbol here, being a tad more accurate than ‘flower’ , and having some contextual evidence to support it.

Knockando had a purpose so important it warranted two quite special symbols, the ‘fire’ symbol and the spoked wheel.

The ‘fire’ symbol has one of the strangest distributions – a line that stretches from the Moray coast, out to the seastack of Dunnicaer, then down to the Fife coast, with just a few on the coast of Sutherland and Caithness. This line isn’t quite a straight line when viewed in close detail, but still, it’s odd, something not seen for other symbols, and a hint that something here demands closer investigation.

The order of the symbol pair

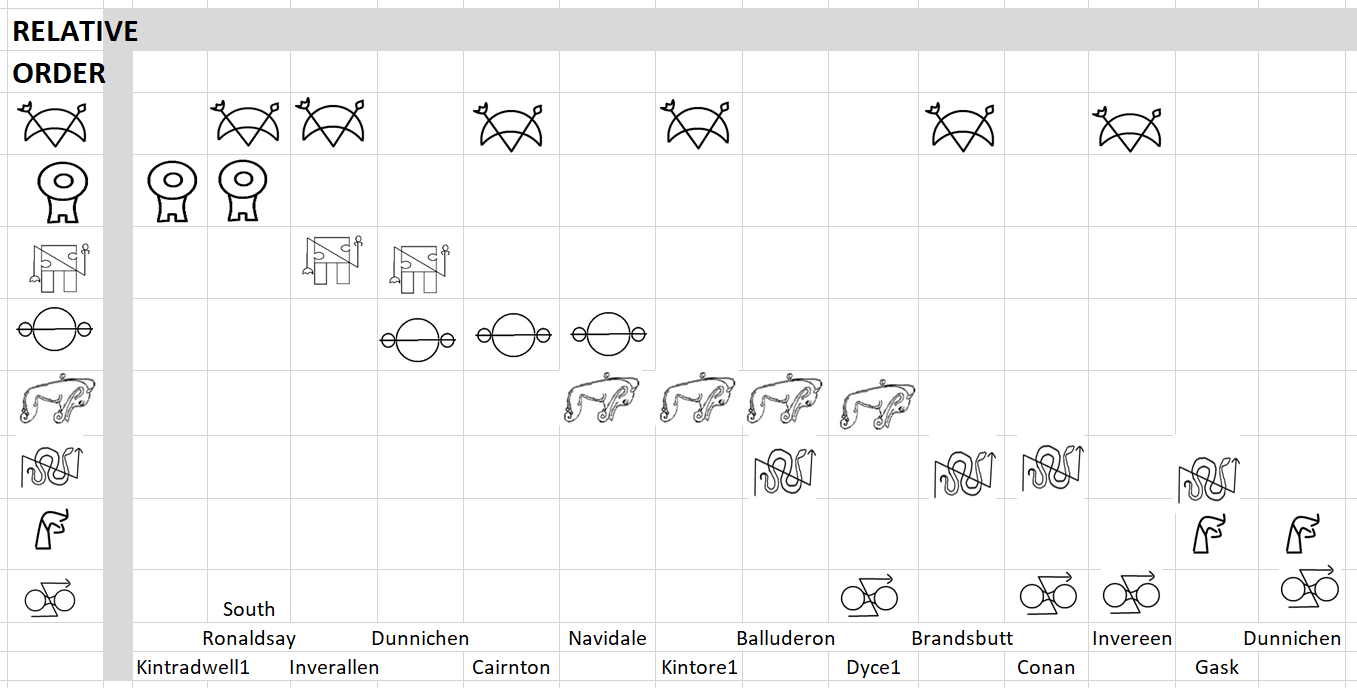

The set of Pictish symbols comes as a list with a natural order to it. The final three symbols on the list are the snake+/-Zrod, the ‘fire’ symbol, then the double-disc+/-Zrod. Whatever the meaning of the symbols, this order has purpose, and therefore meaning, to it as well.

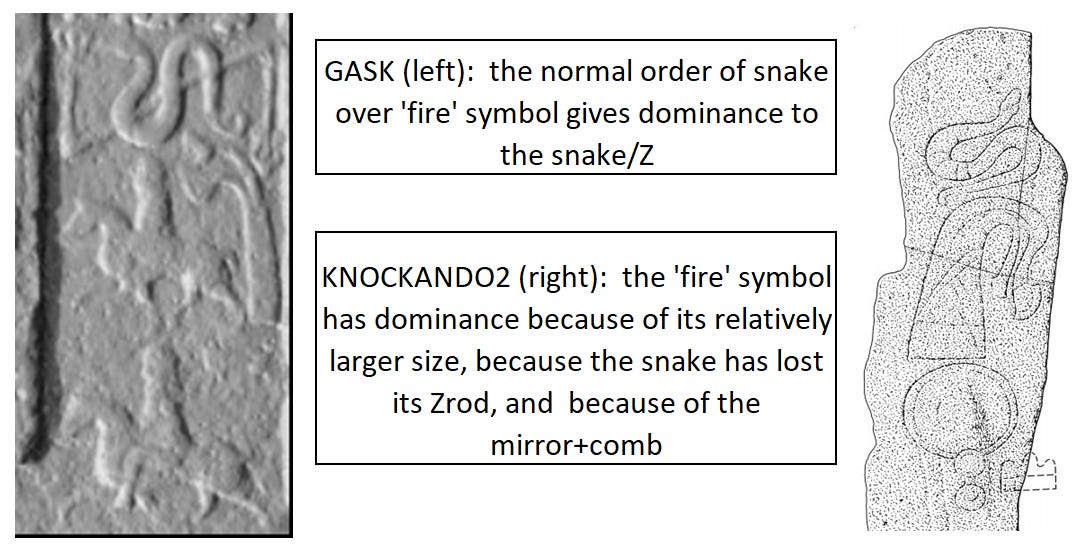

When two symbols are chosen from the list for a particular symbol stone, if they are placed in the same relative order as on the list, then the upper symbol is the dominant one of the pair. Like Knockando2, there are two other stones with a snake and ‘fire’ pair, Gask and Ulbster, both CII stones, but on these stones the snake/Z is over the ‘fire’ symbol, and therefore the snake/Z remains the dominant symbol.

However, on the Knockando stone, the ‘fire’ symbol is given dominance – it is the most important symbol of the pair. This change of dominance can be achieved by a number of methods, and three are used here:

The ‘fire’ symbol is large in comparison with the snake symbol above it (normally both symbols of a pair are of equal size).

The snake has also lost its Zrod, again showing that it is not the dominant symbol on this stone.

The presence of the mirror and comb below the symbol pair again tells us that dominance is on the lower symbol for this stone.

Marking the ‘fire’ symbol as the dominant symbol at Knockando must have some key meaning, but at this point I’m not sure what that is.

The context and meaning of the ‘fire’ symbol

The ‘fire’ symbol quite obviously sits at important ritual sites. It occurs on the walls of a cave full of bones on the Moray coast looking north, a ritual cave packed with skeleton depositions over many centuries and informal symbols, and in a cave on the coast of Fife looking south, again a cave with numerous graffiti symbols implicating a ritual space. Both examples of the ‘fire’ symbol in caves are informal graffiti, and that is also the case with the symbol found on the sea-stack of Dunnicaer, the furthest eastern point on the coast. It is as if people are using this symbol to mark the furthest boundaries of the land.

Another ‘fire’ symbol sits just outside the ritual palisade at Rhynie at the base of the Tap o’Noth with its 800 plus round houses. Another is at Corrachree, a placename that suggests the presence of an assembly place around a sacred tree. Another sits near the top of the hill of Dunnichen, likely considered a localised Sidh of Nechtan, the sacred central source of water. Another sits on Hunter’s Hill, near the important healing well of Glamis, and overlooking the old Lake of Forfar, with a tradition of bonfires being lit on its top. The Gask stone sits close to the end of the Gask ridge on which earlier Roman fire beacons were lit. The Pabbay stone lies at the far southern point of the Western Isles, a logical place for a beacon guiding seafarers.

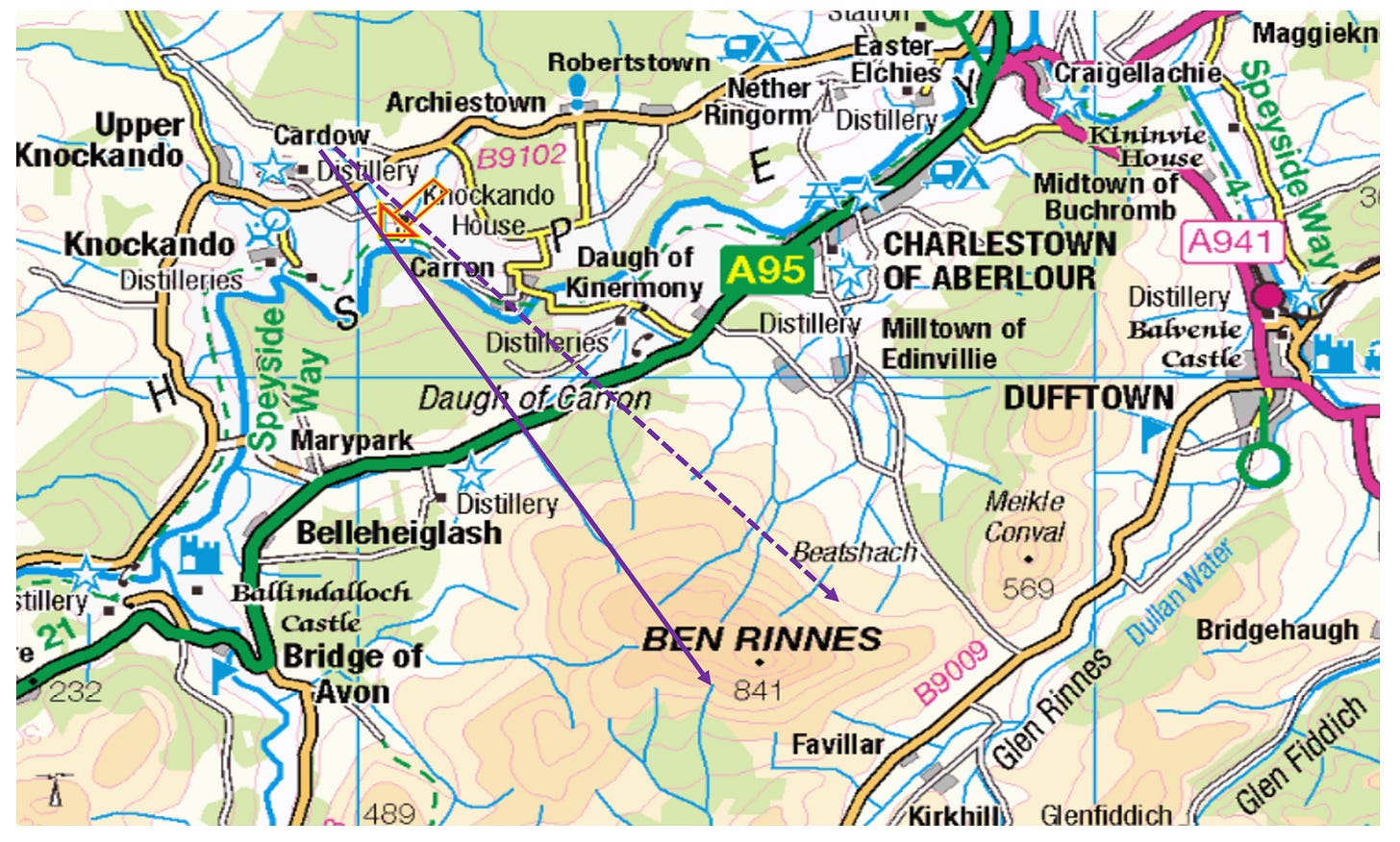

What we can take from these locations, is that the ‘fire’ symbol is not usually located at settlement sites as the bulk of symbol stones are, but at ritual sites, often on higher spots in the landscape, and at least some locations are on record as connected to fire. And so we come back to the situation at Knockando. As I discussed in my previous blog, above Pulvrenan is Newhillock with its ‘Bonfire cairn’. Is this what this symbol is referencing? A relatively high spot, that is still within easy reach of the community. A possible sacred nemeton, a small early church, cairns, wells, a stone circle – and a great outlook over the Spey river valley to the wonderful mountain of Ben Rinnes opposite. A perfect site for a ritual bonfire.

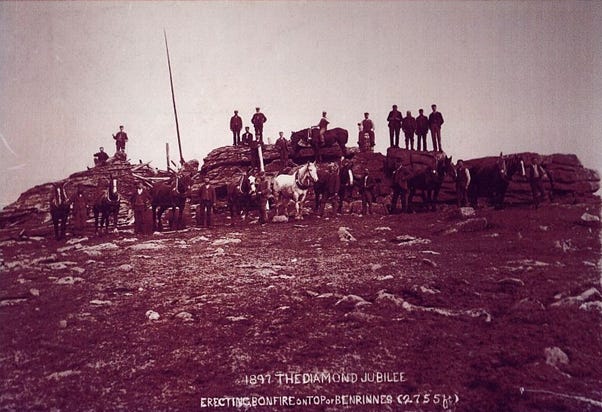

An alternative scenario may be that a ritual fire was built on top of Ben Rinnes itself. It seems a natural thing to do as we see in this photo from 1897.

And this, marking the Queen’s jubilee in 2022:

From the top of Ben Rinnes, the Tap o’Noth can be seen, with its vitrified fort on its summit, and its ‘fire’ symbol below. A fire on top of Ben Rinnes would also have been visible from the Moray coastline, where the next ‘fire’ symbol is found in the ritual caves of Covesea. The idea that the land could be lit up with intervisible ritual fires is exciting, still.

But it also provides us with a clue. If a festival bonfire was lit on top of Ben Rinnes, then it must have been a warmer weather one, not when the mountain was waist-deep in snow and obscured with cloud. This narrows the possibilities down to Beltane (May), Midsummer (late June), or Lughnasad (August).

The odd shape of the symbol

Before I go on, the shape of this symbol, so unusual, yet specific, needs addressing, although here I will only give a short summary. The symbol usually has two ‘leaves’ with an outer crescent (one is no longer visible on the Knockando stone). Ancient axes do have this crescent-shaped blade. Interestingly, two men with these types of axes are also seen on the sun boats of Scandinavian rock carvings, along with the spoked wheel of the sun. One possibility is that these men represent the brothers/sons of the sun, who rescue her each morning from below the horizon, and help her into the day sky. These two men may also be part of the myth of the twins of the sky, the constellation today we call Gemini, and which in Pictish times was the constellation of Beltane. In Irish, Gemini is called the ‘two candles’, which may tie Gemini to the two fires of the Beltane festival.

Why the sanctuary is here

Can we identify what the timing or purpose of such a bonfire might have been in Pictish times? Fires are recorded as being lit at a number of key dates in the Celtic year.

To begin with, let’s try drawing a line from the Bonfire Cairn through the old burial ground of Pulvrenan, where the symbol stones were first recorded. If we then extend this line, it hits the top of Ben Rinnes, suggesting we have an alignment here with the sun and Ben Rinnes. However, the actual horizon line of the rising sun of the winter solstice is shown by the dotted line on the next map below, which seems to appear at the eastern base of Ben Rinnes through the Glack, the marked dip between Ben Rinnes and the Meikle Conval. The problem here is that we need to be standing on the height of Newhillock looking across at a large mountain that the sun is rising beside or behind, so I can’t tell by looking at maps just how the actual event might appear. I need someone on the ground to go have a look and take some photos.

Of course the rising sun of the winter solstice is a major celebrated event from the Neolithic period onwards, so it’s not really surprising to find it here at Knockando.

Funnily enough there are many pictures of the winter sun behind snow-covered Ben Rinnes to be found on the internet. It’s still today a magical sight. And here is the sun rising through the Glack, from the website of the Friends of Ben Rinnes (although it doesn’t say from where the photo is taken or the date).

Which brings us back to the internal decoration (in red) of the crescent/V on the right on Knockando 1, a circle above the gap between two hills – a representation of the sun rising through the Glack?

The winter sun over Ben Rinnes is a wonderful sight, here is a photo take on January 10, 2022, 20 days after the winter solstice. The winter solstice sun will be closer to the top of the mountain.

Alyth and Meigle

Now that we have a possible winter solstice alignment at Ben Rinnes, this reminds us that the Neolithic passage mound, Dowth, with its spoked wheels, also has a winter solstice alignment of its passage, although in this case it is the setting sun. Returning to the spoked wheel as part of the double-disc/Z symbol at Alyth, there is a winter solstice sunrise alignment between Alyth and Meigle, perhaps extending to the top of Kinpurney Hill (although again its impossible to know from maps exactly how this alignment would appear to an observer at Alyth, it needs eyes on the ground! ).

An alternative way of looking at this, is that the alignment from Meigle to Alyth is also that of the setting summer solstice sun - which is fascinating as Alyth has the only known dedication to Saint Moluag below the Mounth in southern Pictland, and his feastday is June 25, a couple of days after the actual midsummer solstice, but when the sun would not yet have noticeable begun moving again. (I wrote more on Moluag here.)

Ardjachie and its spoked wheel symbol

A colleague reading a draft of this blog said, but what about Ardjachie? And why isn’t Ardjachie in the centre of Tain if that is the sanctuary? That gave me a few sleepless nights! In the end I decided to go back to basics, and relook at Ardjachie itself. What I then saw, was a narrow spit out into the sea, but that spit is on another alignment to the midwinter solstice. This reminds me of Stonehenge where the cursus is on a natural formation that happens to be aligned to the solstice.

Not only then is Ardjachie probably some sort of ritual space, but when I extend the solstice line down through Tain and onwards, it lands on the wonderful stone of Shandwick. I was once there near sunset at midsummer, and the sun shines straight down the slope to the stone, so brightly that it was hard to see!

A Lughnasadh festival site

While Ben Rinnes fills the sky to the south of Knockando, there is another interesting hill just to its north, Carn na Cailliche. The Cailleach is the great goddess of the land, and there are several similar conical hills named for her in Scotland. To the west is another, Carn Crom. Now this could just be a ‘crooked cairn’, whatever that could mean, but this is also the name of one of the major Celtic deities, Crom Dubh (and note the dubh again!) Both the Cailleach and Crom Dubh are invoked in Lughnasadh festivals held in early August, a long gathering of several weeks in the lull between summer and winter. The Cailleach is associated with the grain harvest, while Crom Dubh has a festival on the last Sunday of July, known as Dé Domhnaigh Crom Dubh ‘Crom Dubh Sunday’. And so we come back to the placename we saw before on Newhillock, Knock Donach ‘Sunday Hill’. This grouping of the Cailleach, Crom, and Sunday Hill suggests that the Knockando region was also an gathering place where the Lughnasadh festival was held.

A description of the Óenach Tailteann from the Metrical Dindshenchas:

A fair with gold, with silver, with games, with music of chariots, with adornment of body and of soul by means of knowledge and eloquence.

A fair without wounding or robbing of any man, without trouble, without dispute, without reaving, without challenge of property, without suing, without law-sessions, without evasion, without arrest.

A fair without sin, without fraud, without reproach, without insult, without contention, without seizure, without theft, without redemption.

Knockando: a place of assembly

Knockando is a magical place, with Ben Rinnes filling its sky to the south, the river Spey at its feet, the hill of the Cailleach behind it, and paths over hills and along river valleys all converging here.

We’ve seen hints that this place may have been an ancient nemeton, a gathering place, a sanctuary we almost lost sight of, and a focus of later church activity.

Whatever it was called at any time, this is a place sacred through what could well be several millenia. A place to watch the magical moment of the midwinter solstice when the sun rose behind Ben Rinnes than begin its journey back to summer and life again. A place where people gathered from near and far in late summer, a place of joyous games to celebrate the harvest, of huge bonfires lit to greet the sun. A sanctuary, a place of beauty, hope, peace, and wonder.